But hold on! »Drum machines have no soul!« This old reproach is as persistent as any belief in ghosts in the machine. And as, for example, Louis Chude-Sokei has recently shown, it imbues the notion of the machine with a recurrent diehard trauma. Since time immemorial, the »soul« has served as a brutal battleground for negotiations over »humanity,« one on which a white-male-dominated so-called »humanism« has denied a soul to all that it deems technologically or racially »other.« Which is why, when Kodwo Eshun wrote his manifesto More Brilliant Than The Sun some twenty years ago, he celebrated post-soul machinic musics as »anti-humanist« in the emancipatory sense of the term, that is, as a sonic refutation of the endlessly brutal production of difference that goes on in the name of a tremulously soulful »humanity.«

This is also why the ARK drum-machine choir chooses not to pursue a classic, glossy, technoid aesthetic. Once again, the post-soul machine takes a very different path than the chest-beating, macho, and kitsch techno fetishism of long-outdated futurisms – kitted out in crumbling vinyl and fake wood veneers instead of highly polished chrome. The future here is no longer synonymous with a teleological march headed for apocalypse across the killing fields of history. The future now takes the form of rhythmic revolutions per minute in a variety of temporal dimensions. The future is the sheer potential for other and diverse temporalities. Any rhythmic pattern is a form of anti-teleological temporal persistence. It holds (onto) something inasmuch as it keeps it in perpetual motion. And this something thereby also steps out of line. It drifts. Rhythmic time is not hauntologically awestruck by the sublimity of unredeemed futures past. For it knows that such futures always have been, are still, and will forever be nestled in the present.

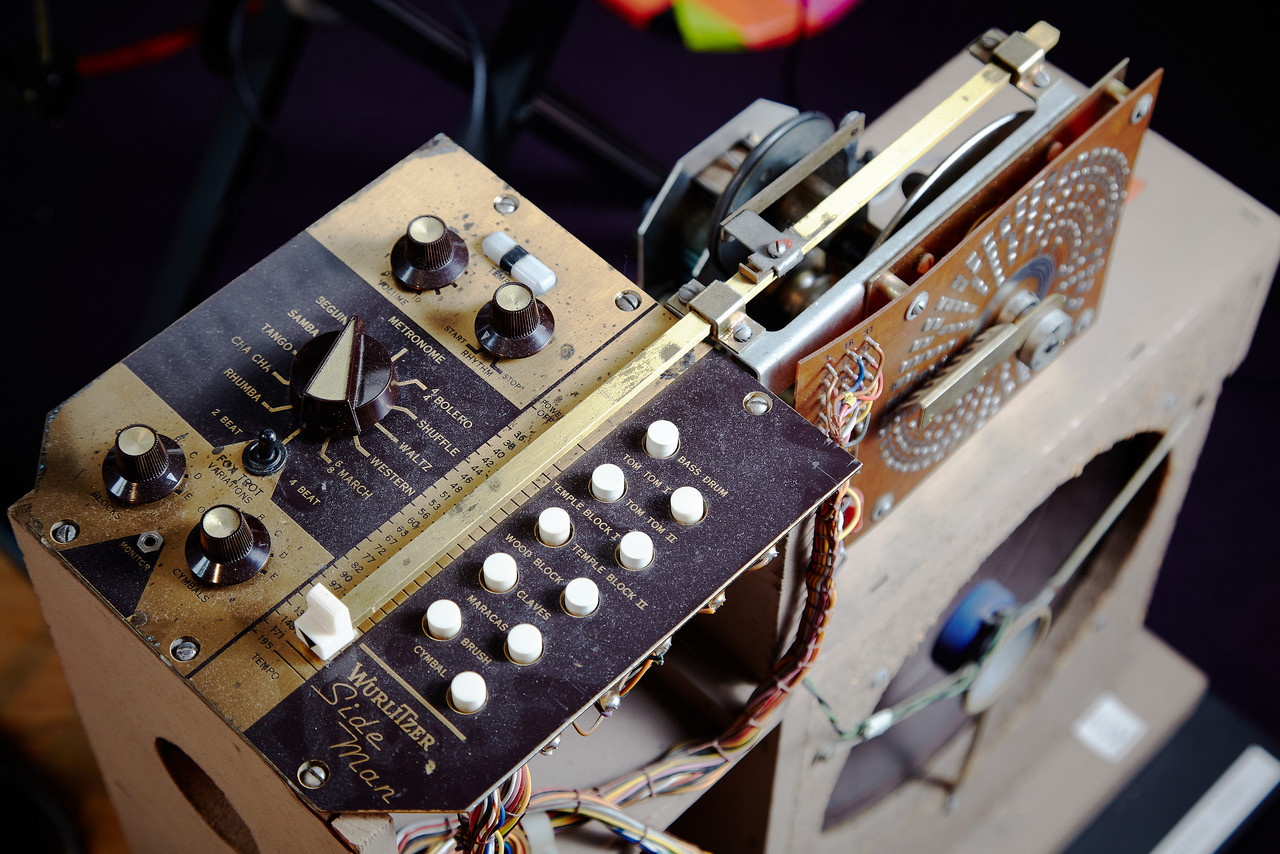

So just what is it that so persistently clings to and pervades these machines, refusing to be dispelled? Which post-soul ghosts haunt their sounds and patterns, or flit around their casings? Perhaps the truly spooky thing about these machines is how much they want us to believe in those little ghosts of their own, within them. Certainly this drum-machine choir invokes the ancient forebears. Long button bars of rhythms conjured on the dusty casing of machines from the 1960s and 70s go under the name »Afro« or »Latin American,« for example. Pre-set categories that, at the mere flick of a switch, neatly divide the world of rhythm into a discrete series of supposedly clearly rooted patterns, and that serve thus to preserve and perpetuate cultural concepts based on a long-obsolete notion of linear genealogy. These simple switches can be read all of a sudden as a postcolonial atlas. They render navigable a wieldy collection of allegedly »roots« rhythmic idioms, put a handle to them, quasi, to make a conveniently packaged takeaway. Lineage and ancestry are newly reconfigured from a pile of transistors, diodes, and resistors. Yet it is precisely this belief in linear genealogy that drives the brutal phantom of distinctions made on grounds of ethnicity and »race« deep into the depths of these seemingly innocent and ingenuous machines. And such distinctions are not found there alone, but also in the latest updates of electronic and digital Musicking Things, the interfaces of which to this day drool with ethno kitsch.

Simultaneously, however, the pattern’s unbroken revolutions per minute or the machines’ incessant operation blurs the latent brutality of such definitudes, or better: even renders them ambiguous. When machines suddenly began grooving in the 1970s – in the hands of Sly Stone or Little Sister, Shuggie Otis or Eddie Harris, to name but a few – »getting into the groove« initially and primarily implied riding high on rhythmic ambiguities. Rhythm may on the one hand mean nothing but taking the exact measure of musical time, but it is this act precisely – that of definitively quantifying time – that allows time itself to be given shape. Groove is accordingly the creative play with and within the ambiguities that occur in the interstices of any strict beat. While the binary counter of classical music theory eradicates such interstices – or in-between spaces, one might say – machinic interplay lets their patterns groove.

Funk has always already been a machine in this regard. And the reverse likewise holds true, as in: technology has always already been funky, inasmuch as it can never be reduced solely to the logic of its circuitry, i.e. to its technologic. So let’s spin that one more time: funk has always already been a machine. Just take, for instance, Anne Danielsen’s work on the pleasure politics of James Brown and Parliament/Funkadelic. Take Tony Bolden’s work on the kinetic epistemologies of funk. Funk has always ranked among the most progressive rhythm technologies ever deployed to interweave several divergent temporal levels in the strictly binary-based logical beat of established music theory. »Everybody on The One!« On the fundamental count of »The One,« everything comes (back) together. Before and after that there is room for all kinds of cross- and counter-rhythmic complexities, but they all come (back) together on »The One.« Incidentally, the Rhythmicon – the first ever electronic rhythm machine that the avant-garde composer Henry Cowell commissioned Leon Theremin to build for him around 1930 – works in a similar yet totally different fashion, simultaneously letting loose sixteen different rhythmic pulses that, as in the overtone series, make an integral multiple of a basic beat. Cowell used the machine to develop a kind of rhythmic harmonics; and he also strove to compose rhythmic constructs of greater complexity than the strict binary counter of the crotchet, quaver, semiquaver, and so on. So let’s hear it now, one more time: funk has always already been a most complex time machine.

The devices assembled in the ARK drum-machine choir are somewhat younger than the still classically modern Rhythmicon, all dating from the 60s and 70s of the last century. And ironically, they do precisely that for which old-fashioned rhythm theory was just – for funk’s sake – reproached above: namely, they measure musical time by a binary beat. An array of proto-digital circuitry is hidden within their veneer-coated wood cases: cascading rows of binary switches that are tasked with the technical translation of the unceasing passage of phenomenological time into a disjunctive sequence of singly addressable points in time. One of the most passionate debates in the philosophy of time is turned into hardware at the heart of these machines, without skipping a beat. Rhythmic time is technical time is switchable time. In the rhythm machines of the 1960s and 70s we find a phenomenon which, in computer technology of that same period, had long-since disappeared below the narrow frequency bands of human perception: time is technically discretised, and at such a speed, moreover, as to span a new (dis-)continuum of technical feasibility above and beyond the gap-ridden sequence of points in time.

Hence, technical circuitry too opens up an interstice, an in-between space that is vastly more complex and diverse than its strictly binary ambiguity ever suggests. Eleni Ikoniadou writes that »[r]hythm may be one way humans have of accessing the subsistence of a more ›ghostly‹ or subterranean temporality lurking in the shadows of the actualised digital event« (Ikoniadou 2014, 7) in this era of universal digitisation, in her view, rhythm – and hence technical time, too – becomes the Geisterstunde (witching hour) of the undead fuzziness of binary code. In the latter’s timing, a specific ghostliness of the still supposedly soulless realm of (not only digital) technology becomes apparent. For after all, even the strictest binary switching takes time, just as the smoothest ever technical processing takes time. But technical operating time, one of the primary features of any technology, is a key guideline for any »human« operational procedures, as anyone who has ever found themselves stuck in front of a frozen monitor knows. Rhythm is haunted by the post-soul Maschinenseele [machinic soul]. What this might mean for sound culture can be gleaned for example from Sly & The Family Stone’s uncanny album of 1971, There’s A Riot Going On. Without his Family Stone, indeed more or less exclusively accompanied by his non-human Maestro Rhythm King – or funk box, as he lovingly called it – Sly rasps his way through a fantastically spine-tingling multi-track duet with himself on »Just Like A Baby,« albeit swathed in the protective drapes of tape noise. The same rhythm machine runs in absolute slow motion also during Shuggie Otis’s spectrally drawn-out instrumental track »Pling,« on his Inspiration Information LP of 1974. Otis stretches to the max that in-between time of the rhythm machine while throwing in some tough and tight Fender Rhodes chords for good measure. And it’s probably nothing other than a Maestro Rhythm King clattering away below the mighty horns on Bob Marley & The Wailer’s Rastafari proclamation »So Jah Seh,« likewise from 1974.

These early forms of machinic music never stood in awe of the shift-shaping ghosts in the machine. They simply played along with them, invited them to join the band, took them seriously as non-human players. Hence the recordings and gigs of that era attest to wholly new collectives built around the machines – collectives that functioned in other ways than the familial model of the band. In 1972, at the height of the Vietnam War, Timmy Thomas sat down alone at his electronic Lowrey Organ with its in-built drum patterns and asked: »Why can’t we live together?« There may be a certain pathos to channelling major questions about the potential for (no longer only human) co-existence through a few trivial technical devices – and yet, on the other hand, Anna Loewenhaupt Tsing’s parable The Mushroom At The End of The World (2017) marks a most urgent endeavour, if not so much to answer these haunting questions then at least to articulate them afresh, for the anthropologist draws artfully on the matsutake mushroom to explore a radical post-anthropomorphic collective. In light of this unlikely candidate, a mushroom that thrives in landscapes disrupted or ruined by capitalism, Loewenhaupt Tsing inquires into what it might mean to live with all the uncertainties that accompany the inescapable co-existence of so-called humankind and all other creatures on a ravaged Planet Earth.

The ARK drum-machine choir makes a similar endeavour but by other means. The machines it assembles are all allowed to bring along the faces and ghosts that stubbornly haunt them. Yet their incantatory revolving patterns sing the praises neither of the motherland nor of ancient forebears but of the critical knowledge circling palpably on their surfaces, detectable in their sounds: a knowledge of the legitimacy of technological agency; a knowledge of the incessant flow of topophilia and the localisation patterns of sound technologies (Ismaiel-Wendt 2011); and, not least, a knowledge of the depredations and traumata spawned by »human« constructions of difference. The rhythm pattern is a non-human memory: rhythmatic random-access memory. Against the backdrop of such rhythmic memories, the currently pressing questions about the potential for new collectives in light of digital cultures may well take a different course. However, the witching hour that the choir announces marks a call neither for techno-utopian hopes nor machinic voodoo likely to appease the destructive forces of technological agency. The ARK choir aims instead to familiarise itself with those distressed and eerie patterns and problems disgorged in the most unexpected places by that »difference machine« known as humankind: those built from a heap of transistors and resistors, for example, and packed into slowly yellowing plastic coatings.