Quellgeister7 is a long-term project devoted to investigating the states of mechanical pipe organs in deserted and derelict churches in Transylvania – organs belonging to a realm that neither nature nor culture can unambiguously define. Over the course of the project I visit them; I seek them out. Why? Well, in order to help them evade the drudgery of serving at the rite of mass, although it has been many years since this obligation weighed upon them. But first and foremost, my intent is to playfully pursue the rapture of their sound and the changes therein, so as to give voice to the relations of non-human language purportedly hiding behind the veil of modernism, in the crypt of this cultural context. Insofar my Quellgeister project is thematically, formally, and conceptually a collaboration – or interaction – between the uncanny and myself. This is evident not least from the series title, Quellgeister, which suggests spectral visitations animated by or within church pipe organs ravaged by the elements and the passage of time. Once bereft of their established sacral acoustic function, these organs become markers of liminality. No longer shackled by human demands, they stand, exposed and expectant, on squares and »wastelands« on the margins of the European present.

While the recording process is about perception of and play with the altered signatures of a pipe organ, my performative practice in Quellgeister constitutes a fundamental acousmatic reverse cosmology. The Quellgeister project participates in the ascension of an abandoned world view. An excerpt from the phenomena implicit in this process is played back, medially – in what I call a non-human mass. And the fact that I’ve had a violent aversion to recording studios ever since I first became preoccupied with electronic music also prompted my quest for new event horizons in the forsaken fortified churches of Transylvania. Within their ramparts, I ask the Lord of the Flies (or Beelzebub, in Aramaic) about the language that has inscribed itself in tongues and the vortex, as well as in the dust dwelling in the organ. It is not for nothing that he remarked in Georges I. Gurdjieff’s Beelzebub’s Tales to his Grandson (1934): »Any writer can write on the scale of the Earth, but I am not any writer.«

»Indeed, this is perhaps the most important question to confront culture in the broadest sense. Let us make no mistake: the climate crisis is also a crisis of culture, and thus of the imagination...so the real mystery in relation to the agency of non-humans lies not in the renewed recognition of it, but rather in how this awareness came to be suppressed in the first place, at least within the modes of thought and expression that have come to dominate over the last couple of centuries.«

– Amitav Ghosh, The Great Derangement (2016)8

Inasmuch as I make a distinction in this context between non-humans and humans, the focus of my observations is the discontinuity fundamental to – and generally acknowledged within – this dichotomy, as well as the consequences thereof, and potential alternatives to it. The separation of nature and culture is established by and through the »autonomous ability of language« (Descola). Separation – the garden fence, so to speak – is likewise the method by which particularity (or particularities) and their attendant nationalism(s) are created. This sort of exclusionary cosmology/ontology is taught to us in schools, perpetuated by the media, and further debated and elaborated in academic discourse. Humans form collectives and differentiate themselves from one another in terms of their respective language and customs – which is to say, in terms of their culture. To the greatest possible extent, they thereby exclude from the thus delimited realm anything and everything exterior to it – nature. This dichotomy of pure and impure sources in »natural cultures« and »cultural natures,« »animate« and »inanimate objects,« »monistic universalism and relative particularities« (Descola) – and, ultimately, of »non-human« and »human« – is fundamental to the founding myth of Western civilisation. Nature is accordingly everything we deem to be external to ourselves, an object that we examine and exploit on the assumption of our own position as subject, an object from which we distinguish ourselves »objectively« and that we supposedly should seek to control.

»But there is now more to gain from trying to situate our own exoticism as one particular case within a general grammar of cosmologies rather than continuing to attribute to our own vision of the world the value of a standard by which to judge the manner in which thousands of civilizations have managed to acquire some obscure inkling of that vision.«

– Philippe Descola, Beyond Nature and Culture (2005)9

Folk music is classified today as a national and cultural phenomenon. However, if we take the separation of nature and culture to be just one variation in this »grammar of cosmologies,« then certain random facts might lead us to suppose that it is nothing but a caprice of the zeitgeist cemented in our minds. Our predecessors were wholly unfamiliar with this model – no ritual music in their day was considered a dogmatically established form of »cultural heritage.« This is why I explore the acoustic states of non-human transformation, thereby predicating music, the discontinuity of which is never-ending and emphatic, because it is composed together with non-humans and unfolds beyond the score of the cultural boundaries inscribed on maps. The church pipe organ is a fitting partner in this sonic investigation of an unravelling of imaginary imperialisms given that this »queen of instruments« was once deemed the very epitome of Western civilisation’s progressiveness in the musical field. Amid this »especial foam« of religious-aesthetic particularity and in light of the Christian-European »church laboratory,« more specifically, of a former German-Protestant ethnic minority, I examine the disappearance of the borders between nature and culture(s). The Heimat (homeland) of a population, hitherto defined in social and geographic terms, here becomes a Heimat anthem from the beyond: human and non-human sound conjoined in the persistence of things. The »well-tempered piano« becomes the »inhuman organ,« but at the end of the day nothing but music happens »to play out abroad.«

»If everybody knows how the machine is functioning – where is the use of it, if we don't know what it is for?«

– John G. Bennett, The Dramatic Universe (1956)10

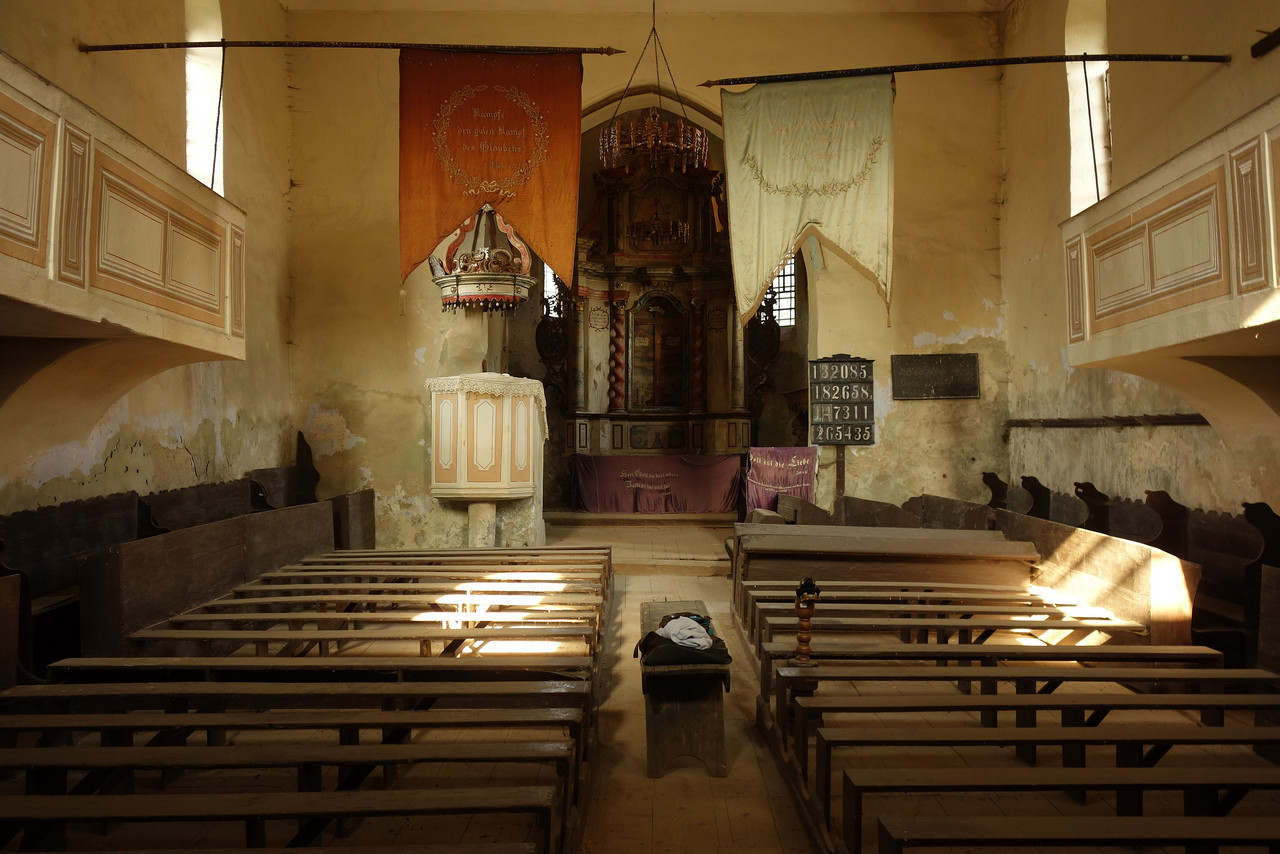

For Quellgeister #2, I investigated the church organ in a Transylvanian village with the German name of Wurmloch, which means wormhole. The organ had been modernised and equipped with an electric motor-driven bellows that would supposedly assure a constant airflow. No such electric bellows has ever been installed in Bussd – to use, here too, the German name for the place where the event horizon of the present ends.11 The organ there – our protagonist in Quellgeister #3 – has barely been altered or modernised since its redesign by the organ builder, K. Einschenk, in the early 19th century. This is why the Bussd bellows is still pumped full of air by human hand while its »inner life« – the wooden mechanism that opens and closes the stops and pallet (valves) — is a filigree arrangement of wooden rods. In the Evangelical Register of Organs in Siebenburgen (to use the German name for Transylvania), the instrument is described as follows: »Action: Registertraktur: mechanical; Spieltraktur: mechanical; classicist in design with painted columns: red-gold-greenish; tin pipes, some front pipes are missing;« and it is said to be overall in an »unplayable/rundown« condition. From the classic viewpoint, this may well hold true, but in my view, this is precisely where the Quellgeisters’ work of alchemy begins. The question being, once the event horizon is reached at last, how non-humans regard and influence our mechanical devices, as well as how they find shelter in them, and thereby wreak change.

»The sixth Quellgeist in the divine power is the sound, tone, tune or noise, wherein all soundeth and tuneth whence ensued speech, language, and the distinction of everything…Thou shall ask, What is the tone or sound? Or how taketh this spirit its source and original? All the seven Quellgeister are generated one in another, the one continually generateth the other, not one of them is the first, nor is any one of them the last; for the last generateth as well the first as the second, third, fourth, and so on to the last…Hardness is the Quellgeist of the tone…And now when the spirits do move and would speak, the hard quality must open itself; for the bitter spirit with its flash breaketh it open, and then there the tone goeth forth, and is impregnated with all the seven Quellgeister.«

– Jakob Böhme, Aurora, (1612)12

Owing to the punctured and decayed state of its air dampers, wooden pipes, and no longer upright tin pipes, the Bussd organ’s air vortex properties in the spatial phase, vortex turmoil, and frequency rotations are not quite what we might expect. Empiric deduction suggests a non-human influence on the properties of these acoustic phenomena. I call the changed air vortex and the spatial phase phenomena to which it gives rise a language from states beyond. The church in Bussd has not been used for celebrations of mass for several decades, and today constitutes an isolated object within the existing village order. In this respect it is practically a neutral temple for celebration of non-human masses.

»And the Horn will be blown; and at once from the graves to their Lord they will hasten. They will say, O woe to us! Who has raised us up from our sleeping place?«

– Quran 36:51 (620)

Eight hundred years ago, a German-Saxon minority followed the lure of tax relief, leaving what is now Luxembourg to make a new home in the village of Bussd, in Transylvania. Successive rulers – from local herding dynasties to Hungarian counts, from Ottoman governors to Austro-Hungarian monarchs – have put their stamp on the human cultural history of the place. Following the demise of the last of them – the multinational imperial and royal »k. u. k.« Empire – there arose around this »organ« the nation state of Romania, which was shortly thereafter steamrollered by National Socialism, before vanishing just as rapidly into the icebox of Cold War-era Communism until, finally, it could be ushered into the Social Darwinist modern times of dog-eat-dog capitalism – although this last instance never really made it as far as Bussd. Descendants of these settlers were able to move to the Federal Republic of Germany long before the Iron Curtain opened – indeed, the West German government paid the Romanian government to allow such Volksdeutsche to leave. They »sought refuge,« as we would say nowadays, in that enticing paradise of »Modern Talking,« a European bastion of freedom and opportunity, and the last of them followed suit after the political turn of 1989. The deserted village was then taken over by Roma families, mainly from the south of Romania. Traditional family ties in their case extend from Wallachia to Turkey, Syria, and Russia as well as into Western Europe. Yet the church organ, now abandoned to its fate by its original benefactors, has found no role to play in these developments.

But physical similarities no longer determine the course of events in the case of Bussd’s church organ, last redesigned and restored by K. Einschenk. As a shifting discontinuity, the language from beyond of the non-humans dwelling in the organ constitutes a sonic relation to the cultural object »human« which, in turn, given its wraithlike appearance, generates a similarity to interiority. Its behaviour thereby is similar to that in its relation to the »language of birds« (Attar). The Quellgeister project draws on mental states and emotional processes to examine similarities in the interiority of non-humans and humans. In societies shaped by animism, there is nothing extraordinary about non-humans speaking in altered states or tongues through human beings. Any subject not distinguished from an object may be found to be in many things.

»Animist subjects are everywhere, in a bird that is disturbed and that, protesting, takes to flight, in the north wind and rumbling thunder, in a hunted caribou that suddenly turns to look at the hunter, in the silk-cotton tree, swaying slightly in a light breeze…Existing beings, endowed with an interiority analogous to that of humans are all subjects that are animated by a will of their own, and, depending on their position in the economy of exchanges of energy and on the physical abilities that they possess, hold a point of view on the world that determines how much they can accomplish, know, and anticipate.«

– Philippe Descola, Beyond Nature and Culture (2013)16

My work on these instruments is no museum piece, no attempt at sentimental restoration of things long since lost to us but, rather, an investigation by means of sound and composition into changes in tonal properties within the body of the organs. The term sonic archaeology springs to mind in this regard, but could prove misleading, just as the notion of science fiction might. For the Quellgeister afford creative potential for a feat of cosmological reverse engineering, a non-human mass, in the celebration of which rings forth the states of a language of signatures. The work accordingly describes »a landing strip for incoming states.« The incoming sonic signatures speak sentences from the »far side of the Horn«17 about the altered states within the acoustic body of the organ. They inscribe the presence of the arrivals in its dust.

Musical intonation began as a sonic representation of a human cosmology, as a conceptual system of relational natural intervals that spurs our emotional states in a coherent manner. In pre-modern times this system was taken to be »the language of angels« (the Brethren of Purity).18 Yet trace the scant available proof and it becomes apparent that relational intervals and the aural spirits flitting between them have increasingly become the »objectified mechanisms« of a naturalistic »interval crisis« (Pleşu) in our self-contained »culture machines.«

The audio material on which the work is based was recorded during two sojourns, in September 2016 and 2018 respectively. In the space of these two years the organ had deteriorated considerably and, undoubtedly, will soon fall silent forever. In 2016 Johanna Magdalena Guggenberger operated the organ bellows by hand-pump and so played her part in interpreting with me the varying timbres that the instrument offered us. In 2018, two children and their father, Antonio – of the Roma family now living in the guardian’s quarters on the outer ring of the fortified church grounds – lent me a hand with this exhausting and challenging task. Pigs roaming the inner courtyard and the entrance to the church were reassuring heralds of the fact that no villager need go hungry in wintertime. And while we worked inside the church on deciphering the signature of non-humans, village life went on outside, as it has always done.

We humans feel it is our prerogative to interrogate inanimate (natural) objects and keep them under close observation, and so we overlook that we ourselves have long been under surveillance by watchful eyes and attentive ears – almost as if our own familiar Earth had become that mind-altering planet painted by Stanislav Lem in Solaris. And who among us can safely say that they have never experienced one of those moments when seemingly inanimate objects suddenly come to life? As when a pattern in the carpet reveals itself to be a dog’s tail – a tail, moreover, inadvertently stepped on… In such moments the call of The Simurgh is suddenly closer than we think.

»All of this [reality] – praise be to God – is in actual fact imagination, since it never has any fixity in a single state. But people are asleep, and the sleeper may recognize everything he sees and the presence in which he sees it, and when they die, they awake from this dream within a dream. They will never cease being sleepers, so they will never cease being dreamers. Hence they will never cease undergoing constant changes within themselves. Nor will that which they see with their eyes ever cease its constant changing. The situation has always been such, and it will be such in this life and the hereafter.«

– Ibn Arabī, al-Futuhat al-Makkiyah (The Meccan Illuminations) (12th century)20

- 1

Here, as also in John Sparrow’s first English translation of Jakob Böhme’s Aurora, which was published in 1656, only forty years after the original, we retain the original German term for source spirits.

- 2

Amitav Ghosh, The Great Derangement (Harayana: Penguin Random House India, 2016), p. 87–88.

- 3

Phillippe Descola, Beyond Nature and Culture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013), translated by Janet Lloyd, p. 87–88.

- 4

John G. Bennett, The Dramatic Universe (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1956).

- 5

...and which happens to be pronounced like the English word »boost.«

- 6

Jakob Böhme, Aurora, ed. Gerhard Wehr (Frankfurt am Main: Insel Verlag, 1992), p. 185.

- 7

Here, as also in John Sparrow’s first English translation of Jakob Böhme’s Aurora, which was published in 1656, only forty years after the original, we retain the original German term for source spirits.

- 8

Amitav Ghosh, The Great Derangement (Harayana: Penguin Random House India, 2016), p. 87–88.

- 9

Phillippe Descola, Beyond Nature and Culture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013), translated by Janet Lloyd, p. 87–88.

- 10

John G. Bennett, The Dramatic Universe (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1956).

- 11

...and which happens to be pronounced like the English word »boost.«

- 12

Jakob Böhme, Aurora, ed. Gerhard Wehr (Frankfurt am Main: Insel Verlag, 1992), p. 185.

- 13

Descola, Beyond Nature and Culture, p. 282.

- 14

This phrase is taken from Ibn Arabi’s Meccan Revelations, Chapter 26: »Concerning the inner understanding of how people remain between this world and the Resurrection.« There, he writes of the Horn of the Imagination, the wahdat al-wujud (unity of being) of which represents the entire conceivable cosmos, creation itself. The manifest part that we are able to physically perceive he describes as »the broad side of the Horn.« »It is breathed into the Horn/forms« (6:73, etc.) and »it is blown upon the Trumpet« (74:8). And the two of them (the »Horn« and »Trumpet«) are exactly the same thing, differing only in the names because of the various states and attributes (of the underlying reality)… Since the Imagination gives form to the Real, as well as everything in the world around it, including even nothingness, its highest section (horn of imagination) is the narrow one and its lowest section is the wide one.« Quoted from James W Morris, »Spiritual Imagination and the »Liminal« World: Ibn 'Arabi on the Barzakh,« POSTDATA, Vol. 15, No. 2 (1995), pp. 42–49 and 104–109.

- 15

Also known as the Brethren of Sincerity (Arabic: إخوان الصفا, translit. Ikhwān Al-Ṣafā), this was a secret society of Muslim philosophers in Basra, Iraq, in the 8th or 10th century CE.

- 16

Descola, Beyond Nature and Culture, p. 282.

- 17

This phrase is taken from Ibn Arabi’s Meccan Revelations, Chapter 26: »Concerning the inner understanding of how people remain between this world and the Resurrection.« There, he writes of the Horn of the Imagination, the wahdat al-wujud (unity of being) of which represents the entire conceivable cosmos, creation itself. The manifest part that we are able to physically perceive he describes as »the broad side of the Horn.« »It is breathed into the Horn/forms« (6:73, etc.) and »it is blown upon the Trumpet« (74:8). And the two of them (the »Horn« and »Trumpet«) are exactly the same thing, differing only in the names because of the various states and attributes (of the underlying reality)… Since the Imagination gives form to the Real, as well as everything in the world around it, including even nothingness, its highest section (horn of imagination) is the narrow one and its lowest section is the wide one.« Quoted from James W Morris, »Spiritual Imagination and the »Liminal« World: Ibn 'Arabi on the Barzakh,« POSTDATA, Vol. 15, No. 2 (1995), pp. 42–49 and 104–109.

- 18

Also known as the Brethren of Sincerity (Arabic: إخوان الصفا, translit. Ikhwān Al-Ṣafā), this was a secret society of Muslim philosophers in Basra, Iraq, in the 8th or 10th century CE.

- 19

English translation from William C. Chittick, Sufi Path of Knowledge – Ibn Arabi’s Metaphysics of Imagination, (Albany: State University of New York, 1989) p. 231.

- 20

English translation from William C. Chittick, Sufi Path of Knowledge – Ibn Arabi’s Metaphysics of Imagination, (Albany: State University of New York, 1989) p. 231.