What to make of Capitalist Realism and the state of music-making for many struggling artists today? Perhaps a day for the average electronic music producer involves trading several hours commuting and working to pay for rent, and not too unlikely anti-social hours working in bars and clubs. The hours set aside for creativity are often snatched, inconsistent, and appropriated from social and leisure times. Adding to further complication, socialising can become more of a dress-down networking event, where the »always on« nature of capital surges through the psyche of the urban club space. The economic malaise of the music industry has been well documented from the emergence of the mp3 up to the end of 2018’s collective backlash against Spotify’s end-of-year playlists, summing up the chasm between social and financial reward as an artist. And yet there is seemingly no end to new producers, thanks to the emergent structures facilitated by cheaper hardware and software, and music platforms providing a lower barrier of entry to share new tracks. Musicians, according to Rosalind Gill and Andy Pratt, »are hailed as model entrepreneurs…conjured in more critical discourse as exemplars of the move away from stable notions of ›career‹ to more informal, insecure and discontinuous employment.«4 The precarity of work in the arts is similar to that of many more emerging employment sectors, most prominently in the so-called sharing economy. However, creative labour entails the exhaustion of one’s passions, leading to fatigue both emotionally and creatively.5

In his conception of Capitalist Realism, Mark Fisher drew on strains of Marxist political theory from Italian Autonomism to Post-Fordism to recognise the blurring of boundaries between labour and leisure, in particular the effects it has on mental health. Labour became flexible in more ways than one; not only does the contract between employer and employee become casualised, but also the nature of communication increasingly becomes transactional, and bonds become temporary. Most noticeable of all, labour is internalised. As a case study, the UK’s employment figures are massaged and plugged by an increase in self-employment, the most casual and least protected working sector. »Work and life become inseparable. Capital follows you in your dream. Time ceases to be linear, becomes chaotic, broken down into punctiform divisions. As production and distribution are restructured, so are nervous systems…you must learn to live in conditions of total instability, or ›precarity,‹ as the ugly neologism has it.«6

The noticeable rise in mental health awareness, in music but also more broadly in society, is not necessarily a thing to celebrate. Yes, it is positive progress to recognise such illnesses as stress, anxiety, and depression as legitimate diagnoses which can be as debilitating as more physical, visible maladies. However I sense a particular nefarious undertone in the narrative afforded to mental health issues in the public eye. The rise of »mindfulness« and self-care strategies, twinned with sensationalist media campaigns on musicians opening up about their woes (although the destigmatisation through celebrities provides key icebreakers in the conversation) obfuscate the debate over stagnating living conditions for a generation. For many, practicing mindfulness proves to be a necessary coping mechanism for high-pressure work and living conditions. But who can afford to take time off and meditate? To what extent is mindfulness designed as self-improvement not only for one’s own needs but also for the creation of more mental resilience in the face of ever more exploitative labour practices? Aisling McCrea posits that »the rhetoric around self-care is flattering but flattening, treating its audience as though the solution to their problems is believing in themselves and investing in themselves. This picture glosses over the question of what happens when society does not believe or invest in us.« Not only does mindfulness demand a form of labour on the self, but it also turns its patients into consumers, supplementing their lives through short-term fixes, from short breaks to health apps.

McCrea asks: »Why are these feelings familiar to so many of us, yet we feel so alone?« Refocusing on the musician, what impact does production and performance have on our mental health? What impact does it have, particularly on the surge of solo artists, producers, and DJs who, on one hand, have benefitted from computer music-making, yet, on the other, have ushered in the atomisation of creativity, after the wreckage of the music industry at the beginning of the 21st century? Without lamenting too heavily on the decline of the band, one might suggest that the replacement of group collaboration with an emphasis on individual personal expression may lead to an increase of isolation in art. The Quietus’ 2016 research into mental health in music showed a 10-20% difference in anxiety and depression sufferers between solo artists and band members. Working alone in electronic music is nothing new, with over three decades of solo producers and DJs making the canon, however with the democratisation of audio workstations making creativity more accessible than hiring studios, rehearsal spaces, and affording musical instruments, isolation is quickly becoming the norm for contemporary Western music practice. Furthermore, when creative isolation becomes more ubiquitous both in music and in other knowledge-based labour, one of the few options presented to us seems to be atomised self-care.

Loneliness is often allayed, in Western culture at least, within a framing that sociologist Eva Illouz defines as emotional capitalism. When registering the emotional intelligence of voice assistants, Siri is described as »a regime that considers feelings to be rationally manageable and subdued to the logic of marketed self-interest. Relationships are things into which we must ›invest‹; partnerships involve a ›trade-off‹ of emotional ›needs‹; and the primacy of individual happiness, a kind of affective profit, is key.« Furthermore, wellness in emotional capitalism fuels the industry of self-optimisation, from becoming more effective in the workplace to expressing your best self in social situations. Art and music, as digital and physical practices, can intervene in our mindfulness malaise – and this may prove to be a key to how we might escape emotional capitalism.

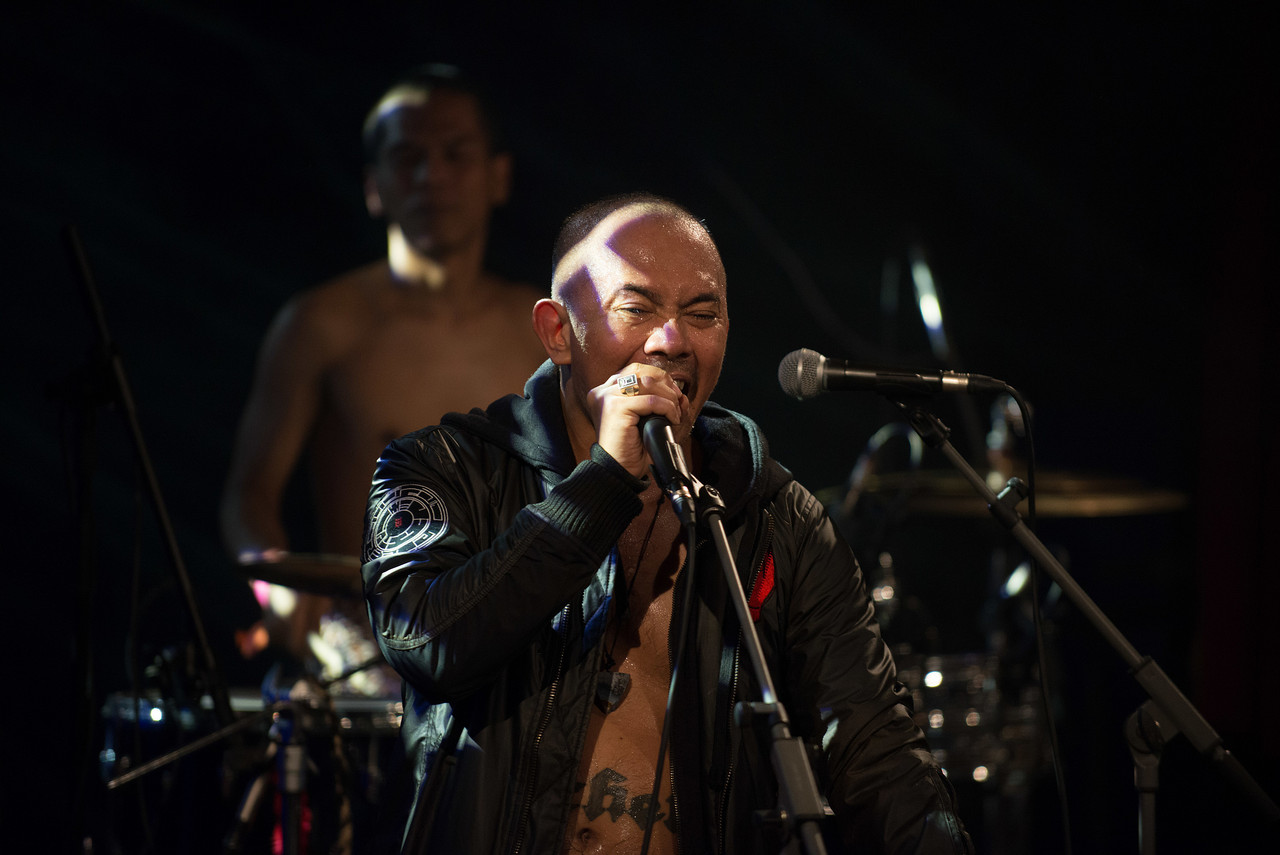

Reinvigorating forms of solidarity in music mark a strategy for wellness, not just for oneself but in order to support one another. The dynamics of improvised music within a group, for example, demonstrate ways of communication and care in which the sonic outcome is dependent on the constituency of the group. As David Bell notes, improvisation as a radical practice »collapses the binary opposition between the individual and the collective: the ability of one to act from their position of difference increases the ability of the collective to act.«8 Rully Shabara’s improvisational practice explores consciousness-raising through communicating musically with different performers from various traditions, as well as responding to his environment. With Senyawa (roughly translated as »chemical compound«), his semi-improvisational compositions with Wukir Suryadi are inspired by a dialectic between man and nature, while Ruang Jagat invites audience members to try their hand at exploring their voice through conducted orchestras.

Similarly, Pauline Oliveros’ Deep Listening practice encourages a heightened sense of consciousness of sound to open up human dynamics of attention. However, her Sonic Meditations group embodied a more concrete political approach in that the initial group was a women-only formation. Throughout much of Oliveros’ work, her aim was to »to create an atmosphere of opening for all to be heard, with the understanding that listening is healing.« Music demands resonance, empathy, and space to be heard, in the same way the politicised, marginal body seeks freedom of expression. Working with dancer Elaine Summers, Oliveros’ Meditations focused on exploring the movement of bodies together in a space. After hosting private weekly improvisation groups, Oliveros began sharing her Sonic Meditations practice through print in order to share her work as a form of activism. According to Kerry O’Brien, Oliveros’ Sonic Meditations shouldn’t be mistaken for escapism or disengagement. The composer described listening as a necessary pause before thoughtful action: »[l]istening is directing attention to what is heard, gathering meaning, interpreting and deciding on action.« For Oliveros, music’s symbiotic action of listening and performing was key to healing oneself and each other.

These collective experiences, be they in the workshops conducted by Pauline Oliveros and Rully Shabara, or in groups of individual performers, such as London’s Curl collective, serve a timely reminder that collaboration can help musicians out of isolation, whether through meeting up in physical and virtual space to communicate abstractly; to absorb, explore, and embody other ideas outside the hermetic reach; or to simply have fun in making sound. In the example of Curl co-founder Coby Sey, eclectic output is defined by a desire to make conversation through challenging his practice – he works alongside a broad array of artists from Mica Levi and Dean Blunt to Tirzah, Ben Vince, and Hannah Perry. From there broader solidarity can occur, posing questions as to why these experiences are sometimes not afforded to us, particularly in politically and economically complicated spaces. Along with Sey’s work, which makes nods towards the long struggle against austerity in Britain, music has always been a battleground for political and cultural bodies in space. During 2018’s Lisbon Pride, DJ and producer Violet invited queer collective mina to invade the stage in protest of the lack of visibility for transgender people during the event, while Moscow duo IC3PEAK publicly challenged the Russian government’s authoritarian stance on sexuality through live performances and the dissemination of provocative music videos. These moments serve to spark discourse and struggle, however activism in music extends beyond events and towards building more solid foundations of solidarity and community.

Traces of Oliveros’ feminist activism from the 1970s in the spirit of Sonic Meditations can be found in the current wave of production workshops, such as Mint and No Shade in Berlin and Femme Electronic (hosted by DJ Rachael) in Uganda, which use music practice to build womxn-oriented communities. These workshops emphasise the listening experience as central to mixing records, training DJs to carefully select tracks that flow from one another, to create unlikely kinships from track to track, and to respond to the dancefloor, controlling the momentum and giving a platform to as-yet unheard musics. Workshops give spaces for womxn to not only develop their skills but to foster communities. »I felt that women DJs were missing…they were invisible,« said DJ Rachael to Vice Magazine. »I also thought they would be stronger as part of a group than being solos, as it has always been.« Safer spaces have increasingly become a tactic in the face of rising or already-existing xenophobic, homophobic, and patriarchal oppression, creating alternative welfare networks. With the recent reports of sexual assaults at music festivals conducted in the UK as well as the demand to diversify clubs and venues, the demand for safer spaces has never been more urgent. London nights such as Pussy Palace and Body Party have initiated safer-space policies through an intersectional approach, ensuring that queer black bodies are protected at their venues. These spaces are still precarious, and dependent on occupying commercial spaces which can only exist if the spaces are attended regularly.

However, precarity, if held solid long enough, can sow the seeds of more permanent accommodation. Bassiani, Tbilisi's best known night club, provides an apt example of musical space acting in defiance of wider structural forces, creating kinship not only within Georgia’s countercultural scene but also through visiting performers, collectives, and scenes. Housed underneath a Soviet-built sports stadium, Bassiani was established as soon as founders Zviad Gelbakhiani and Tato Getia could find a venue big enough, acting as a space for alternative culture as well as housing LGBTQI+ club Horoom. However this past year has seen accusations and raids conducted by the Georgian government over their supposed responsibility in drug-related deaths, despite the fact that none of them occurred at Bassiani. After the club was violently raided and shut down by the police, over 10,000 people took to the streets to stage a rave and demand the resignation of prime minister Giorgi Kvirikashvili and minister of internal affairs Giorgi Gakharia. The organisation of the protest was in no small part assisted by social media, with participants broadcasting their activities to local and global networks, as well as distributing footage from the raids to online magazines in order to mount pressure on the Georgian government.

New forms of activism have not only built upon traditional forms of protest, but also serve to remind us of the possibility of intersectional support and dependence on one another. Such strategies include creating swarms as spontaneous collective action from specialised hackers and organisers, or assembling weak networks on popular social media platforms, with which to share information and one-off campaigns between disparate individuals and groups. Weak networks, while perhaps allowing us to fall further into issues arising from popular social media, from the capture of personal data to discerning the broadcast of information between free and sponsored posts, have also allowed for activism to spread worldwide.11

Taking vulnerability as a shared position, as demonstrated by maintaining safer spaces, sharing activities, and supporting campaigns directly or indirectly, is, according to Judith Butler, a resource for common wealth. Of course it would be preferable for such communities as LGBTQI+, refugees, ethnic minorities, the disabled, and the unemployed to be afforded autonomy equal to cisgendered and patriarchal beneficiaries. However, in considering Butler’s suggestion that »to say that any of us are vulnerable beings is to mark our radical dependency not only on others, but on a sustaining and sustainable world,«12 we invite ourselves to open up and resonate with others through shared needs. Precarity calls upon a broadening interdependence and the call for creating coalitions between people, a direct contrast to the neoliberal world of individualised and competitive bodies. By noticing each other’s vulnerabilities, we may find room for each other in music-making and scene-building to ensure everyone is not only included, but given time and space to find one’s own solid foundations.

Of course it would be naive to expect music to solve all the demands of the contemporary world and its emotional and mental strains. The production and enjoyment of music is especially compounded now that music is becoming more ubiquitous thanks to streaming platforms, simultaneously sculpting our increasingly work-oriented environments into what Paul Rekret calls »a contemporary chill ground zero,« while extracting data capital from our leisure time. While there is a discussion to be had about the wider net of Capitalist Realism, we can certainly ask what music can do to raise consciousness, a central tenet of Mark Fisher’s unfinished Acid Communism project. In certain camps Acid Communism is seen as a rehabilitation of countercultural utopianism, from communal meditation to discussion groups, while others see a more radical and philosophical construction of the Other. Acid Communism could be broadly seen as a reassessment of the materials and histories at hand, an effort to remould all senses of community and intersectionality. This could range from pragmatic strategies of connecting digitally with ourselves and others to create networks of solidarity, to taking inspiration from improvisation and learning how to explore boundaries and relationships fluidly, or even forming groups of precarity that allow time and space for people to be heard. Music can be a part of all of that. Channelling Butler, Mark Fisher wrote about consciousness-raising: »[t]he roots of any successful struggle will come from people sharing their feelings, especially their feelings of misery and desperation, and together attributing the sources of these feelings to impersonal structures.«

- 1

Gill, Rosalind and Pratt, Andy, 2008. »In the Social Factory? Immaterial Labour, Precariousness and Cultural Work,« Theory, Culture & Society, 25 (7-8), pp. 1-30.

- 2

Ibid pp. 15-16.

- 3

Fisher, Mark, 2009. Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? Zero Books, Winchester, UK, p. 34.

- 4

Gill, Rosalind and Pratt, Andy, 2008. »In the Social Factory? Immaterial Labour, Precariousness and Cultural Work,« Theory, Culture & Society, 25 (7-8), pp. 1-30.

- 5

Ibid pp. 15-16.

- 6

Fisher, Mark, 2009. Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? Zero Books, Winchester, UK, p. 34.

- 7

Bell, David, 2012. »Playing the Future: Improvisation and Nomadic Utopiania,« Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, UK.

- 8

Bell, David, 2012. »Playing the Future: Improvisation and Nomadic Utopiania,« Centre for Contemporary Arts, Glasgow, UK.

- 9

Stalder, Felix, 2013. Digital Solidarity, Mute/Post Media Lab, Lüneburg, pp. 40–50

- 10

Butler, Judith, 2015. Notes toward a Performative Theory of Assembly, Harvard, p. 150

- 11

Stalder, Felix, 2013. Digital Solidarity, Mute/Post Media Lab, Lüneburg, pp. 40–50

- 12

Butler, Judith, 2015. Notes toward a Performative Theory of Assembly, Harvard, p. 150