1.

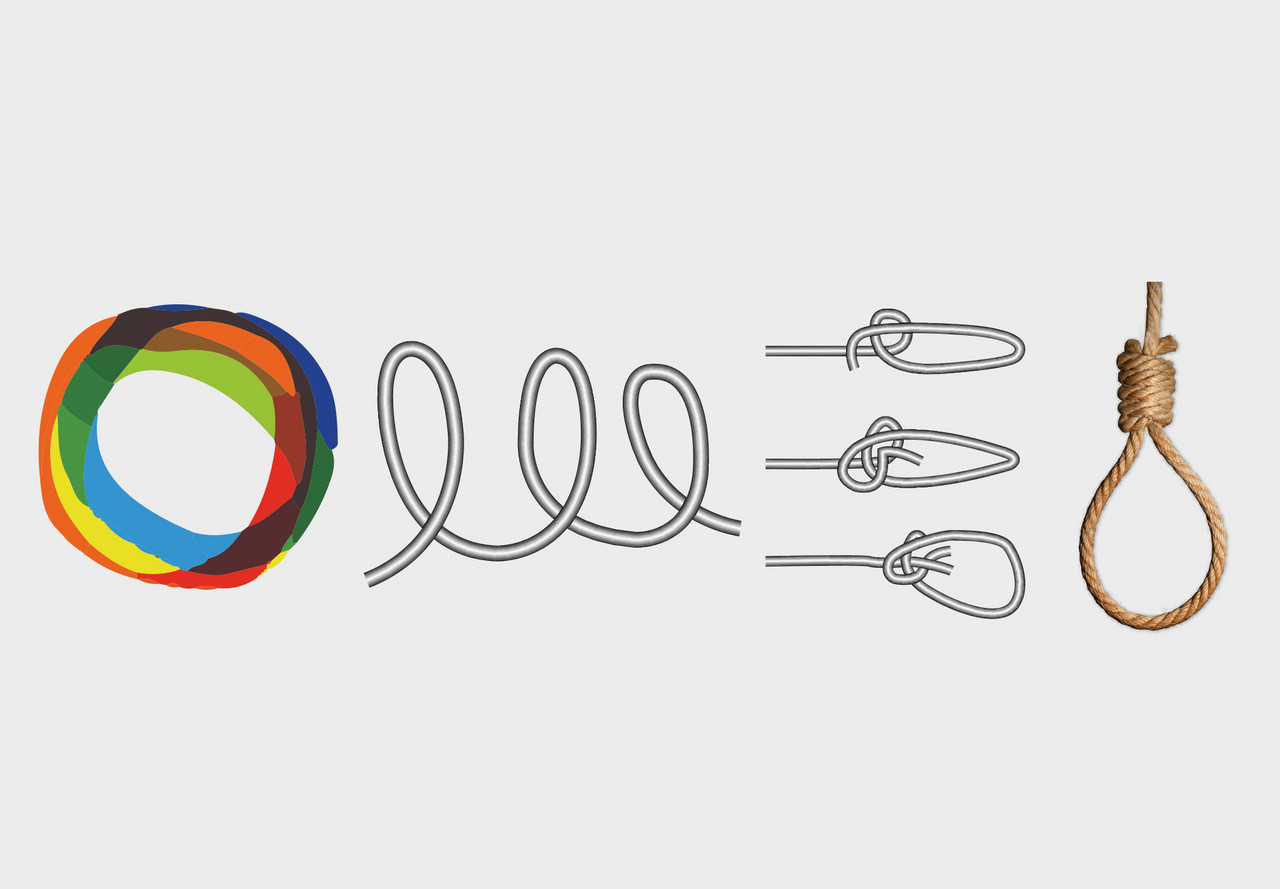

A loop is a shape produced by a curve that bends around and crosses itself.

A loop is any structure or process in which the end is connected back to the beginning.

A sequence that repeats by returning to the position it started from.

A closed circuit.

For the nearly 300 million people around the world who have currently left the land of their beginnings, their end is not back from where they started from. For so many forced to move, to leave, whether because of political terror or economic impossibility or climate catastrophe – 26 million refugees and asylum seekers among them, roughly the population of North Korea or Madagascar, more than the population of Hungary or New Zealand or Jamaica or 200 other countries around the world – the loop is a wish, a goal post, a dream.

The reality is an incomplete circuit, a shape produced by a curve that never bends around itself, that never crosses itself. A beat that never returns to its beginning. A feedback loop that is all feedback.

What is the opposite of a loop?

A line? A boundary? A border? A wall?

A return that is always deferred.

A forward motion, a propulsion, that never ends, either because the movement never stops, or because the movement is stopped – at borders, at checkpoints, in detention centres, in prisons, in the desert, in the sea.

This is no world of loops. Think of that long curving bending line of thousands of Central Americans walking north across Mexico who did not want to return home, now halted indefinitely in Tijuana by clouds of tear gas and barricades of riot gear and razor wire at the most-crossed land border in the world that – at the Tijuana-San Ysidro crossing alone – regulates a 2.1 million dollar a day cross-border economy.

Think of generations of Palestinians – the unending refugees of this century and the last – who want the right of return, and whose existence is defined by the denial of that right. One day, Fairuz still sings, we will return, return, return, return. Regardless of the length of time and distance that separates us.

The right to loop. The privilege to loop.

There are those who want to return and cannot. There are those made to return, processed, detained, sentenced to months and years in tents and camps, added to watch lists, sent back, deported, denied entry, who don’t want to return.

The loop is the political dream. But the loop is also the punishment.

Much of the commercially produced and available music in the world today is made of loops: a breakbeat that is made to repeat as a pattern, a sample of a politician uttering a declaration, a trumpet squeal that keeps squealing. Loops become the foundation for composition, a bedrock of patterned knowledge and information that, through its sonic architecture of repetition, allows new possibilities to emerge, new choruses to erupt, new bridges to connect verses and phrases. Beyonce likes loops. J Balvin likes loops. CTM is unimaginable without loops. In Lampedusa this past spring, I heard loops everywhere – reggaetón and Arabic trap bumping from car speakers. In London, I heard loops in Afro Bashment burners and Indian new school jazz and industrial oud experiments. In Tijuana, Haitian rappers use loops to make sense of how far they’ve come from a home they are no longer trying to return to: a music of loops for a population that cannot loop.

The loop is just one way to explore how global displacements and expulsions have changed the way the world sounds. As a result, I’ve been listening for the sonic aesthetics of displacement, the music of dispossession, the sound that forced movement makes, or, as Philip Bohlman put it, »the importance of music as a measure and medium of displacement.« Music as a form that migration takes.

There is no music without movement, of course, no conception of sound without the event of two opposing forces moving towards and into each other to create vibrations in the air. Music, to sample and flip Q-Tip, is a mig’rant thing, a migratory thing, a movement thing. So we need a new kind of listening, one that listens for the politics and hierarchies of these movements, their uneven flows and policings. Let’s call it, in the spirit of Walter Mignolo, Anibal Quijano, and Rolando Vazquez, a listening attuned to the coloniality of power, a border listening.

»Borders have changed place,« Etienne Balibar has written. »Whereas traditionally, and in conformity with both their juridical definition and ›cartographical‹ representation as incorporated in national memory, they should be at the edge of the territory, marking the point where it ends, it seems that borders and the institutional practices corresponding to them have been transported into the middle of political space.«

What does this new global borderscape sound like? What does colonial divestment sound like? What is the sound of rights? Hannah Arendt famously argued, from a 20th century position of displacement and exile that echoes similar positions from this century, that politics is the space of appearance and the legislation of a right to appear. The loops of contemporary sonic culture provide the foundation for an exploration of sonic rights, of a right to sound, to listen, and to be heard.

»If you had the freedom to get in a car and drive for an hour without being stopped (imagine that there is no Israeli military occupation; no Israeli soldiers, no Israeli checkpoints and roadblocks, no »by-pass« roads…)« the Palestinian artist Emily Jacir asked fifty Palestinians in 2008, before the Separation Wall made daily commute loops across Jerusalem unsustainable, »[w]hat song would you listen to?«

What sound would you listen to if you could be free?

Most definitions of a loop remind us of its shape: curves and bends that always create an opening.

And yet, one of the word’s etymological roots comes from the 14th century, when a loop was also a word for noose.

A shape of life that is also a shape of death. Decomposed in the Mexican desert. Lost in the waters of the Mediterranean. Blown to bits in Gaza.

I recently heard an invocation by Father Gregory Boyle, the founder of Homeboy Industries (a job training program for the recently incarcerated and former gang members), ask the world to draw a circle of compassion so wide, so large, so ample, that there is nobody who stands outside of it.

A loop of compassion so wide, so large, so ample, that the circle can only be an opening, a start, an embrace, and never a noose.

Never a noose.

On loop.

2.

To fade is to lessen in intensity, to diminish, to become less bright, to move into darkness, to become invisible. »We see what happens when we persecute people,« Mahershala Ali said. They fold into themselves. Fading and folding in; folding in as a kind of fading out.

The crossfade, though, the crossfade never lets the less bright take over. It folds out, it moves into the light.

Section 9.13 of the 1977 sound engineering manual Audiocylepedia:

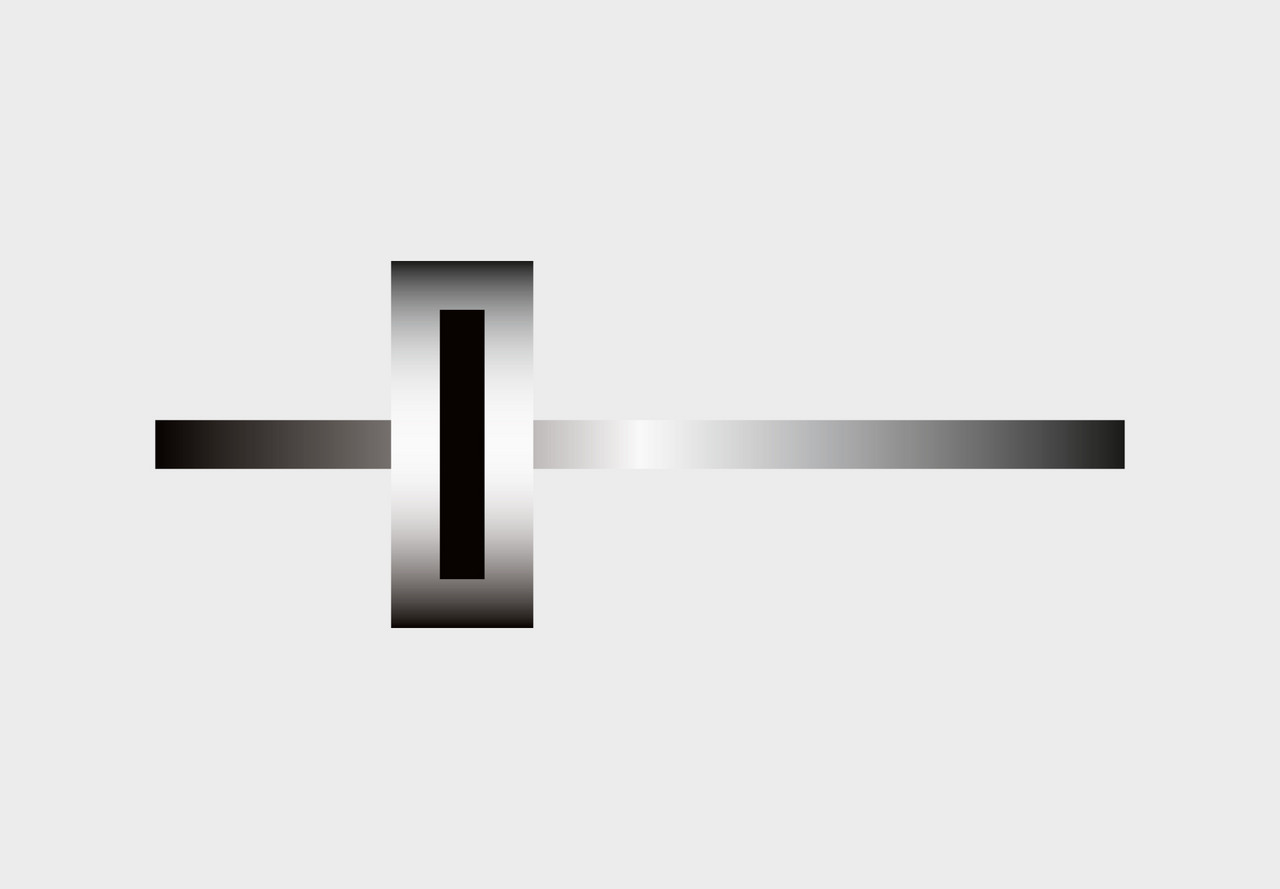

crossfade. verb. »The gradual attenuation of one signal as another is gradually brought up to normal level. This is accomplished by closing one mixer pot as another pot is being opened.«

Richard Wadman, the British engineer who created one of the first crossfaders on the SMP101 mixer, didn’t see it as a strictly musical tool. It was a solution to an energy crisis: how to sustain energy in the face of its diminishment? How to sustain flow and current when moving from one source to another, how to move from left to right to left to right to left without losing your step, your bounce, your beat. How can the uninterrupted flow of energy save us? How to mix without erasing? How to sustain life in the face of the loss that always threatens to take it over?

At roughly the same time, in the South Bronx, Grandmaster Flash was answering the same questions when he wired his own horizontal crossfader into his DJ mixer to perfect the beat science of connection within his theory of the Quick Mix. He used the crossfader to juggle breakbeats, cut them up with scratches, and create loops that kept bodies moving and bending and breaking.

At roughly the same time, at Harvard University, George Steiner got on the mic to remix T.S. Eliot’s Notes Towards the Definition of Culture. Born into an escape from Nazi Europe, Steiner called his exilic edit »Notes Toward a Re-Definition of Culture« and this was a sample he flipped:

»The new sound-sphere is global. It ripples at great speed across languages, ideologies, frontiers, and races. The triplet pounding at me through the wall on a winter night in the northeastern United States is most probably reverberating at the same moment in a dance hall in Bogotá, off a transistor in Narvik, via a jukebox in Kiev and an electric guitar in Benghazi. The tune is last month's or last week's top of the pops; already it has the whole of mass society for its echo chamber. The economics of this musical esperanto are staggering. Rock and pop breed concentric worlds of fashion, setting, and life style. Popular music has brought with it sociologies of private and public manner, of group solidarity. The politics of Eden come loud.«

By the end of the 1970s, the crossfader had become a method and a politics, a new way of music-making but also a new way of living. To crossfade is to mix without erasing.

To openly pursue the multiple, not the singular; the both/and, not one or the other. To listen for points of connection, moments of commonality, starting points of solidarity. To crossfade is to sustain difference. To listen carefully to sounds that already exist while imagining sounds that have yet to exist, to juggle past and future within the time signatures of the present. To crossfade is to listen for edges and borders, not centres, the places where the lines blur, where languages trade tongues, where geographies meet. To crossfade is to suture and cut, suture and cut. To crossfade is to live multiple realities at once, playing one while cueing up another, playing one and fading it to another, finding a new mix for life.

The crossfader knows:

we are not single inputs

we are samples

we are constellations of place, broken locations, dislocated maps

we are each a matrix of conditions, waiting to become part of another matrix of another set of conditions

we are here to be connected

The crossfader is an anti-assimilation technology. The crossfader chooses the mix over the melt, the many over the one, the pluribus over the unum. The crossfader is German and Syrian, Algerian and French at once, at once, never needing to abandon one for the other. What a time to be crossfading, across fortress Europe, in the age of the AFD and Orbán and Trump and Netanyahu and Bolsonaro, across militarised deserts, across the former West and the former East, the former North and the former South.

The crossfader looks linear but it actually operates on a curve. Bending and arcing like justice – open and closed, closed and open, keeping the beat going across our walled, walled world.