Recall the opening night of CTM 2018, exactly one year ago now. Upstairs in the recently opened Club OST, noise-punk idioms erupt in a shuddering, sizzling mass. Berlin trio Cuntroaches are heating things up. The band is loud, and between each number, feedback sears the air and snaps at buttocks. There’s a hint of truculence, too, with newspapers torn up and stuff chucked into the audience (before being thrown back). After 20 minutes, it’s all over – but there’s something weird about this too. Something doesn’t seem to fit in the venue. Is the audience too attentive? Has it failed to comprehend the Fuck You message? Or is it still waiting expectantly, unable to sense the music’s inherent urge to destroy?

For five euros we grab a cab from Club OST that takes us back in time to Koma F, where Cuntroaches had played some months earlier along with Polish hardcore band Ohyda. Koma F is one of several cellar clubs in the Köpi complex, a place that wears its 28-year history on its crusted sleeve. It is a time capsule in which layer after layer of history settles democratically, a convulsive organism whose animal magnetism has pulled in generations of outlaws and exiles – and partied with them too, as Jabba the Hutt and his crowd do. It’s a dark descent into Koma F. The familiar feedback of Cuntroaches rips through the wall of indefinable odours. Apart from the shredded newspapers, Cuntroaches do nothing differently here. And yet the room is crackling with raw energy; bodies glow, and after each electrifying jolt, embers smoulder with relish like the reactor room on the USS Thresher.

There is a point to this juxtaposition, of course – to examine these two spaces side by side. CTM is a festival, built to neutrally showcase whatever content is pumped into it; Koma F is an emotional multiplier that raises mercury exponentially once action hits its peak. Socio-economically, of course, both spaces operate within complementary sets of rules. The crucial point is what melds them, namely their common aspiration to give audiences a unique experience a million miles removed from the everyday. Urban sociologists have long been researching Berlin’s autonomous zones since the 1990s – and you need look no further than the history of CTM itself to understand how essential these zones and spaces are to festivals. Spaces like Koma F have emerged from a tradition-bound sociosphere that is neither likely nor (in principle) even remotely willing to receive any form of state support. How such spaces function and persist today, in 2019, can only be explained phenomenologically if at all.

From Southwest Essex to New York

It’s the early 1960s and Penny Rimbaud, a sheltered middle-class kid from Northwood, Middlesex, has just graduated from art school. He works briefly as an art teacher and then, following a successful exhibition in 1964, turns down a job opportunity in Andy Warhol’s Factory, claiming he has better things to do. Inspired by Pop Art of the early 1960s, socialised by Bauhaus and Fluxus, and radicalised by the Situationist International, Rimbaud founds a commune with his pal Gee Vaucher in 1967. Residing at Dial House, a farm in southwest Essex, it is one of the first independent anarchic-pacifist-oriented centres in shared use and under collective management. Dial House helps propel a handful of seminal festivals that have the character of happenings – The ICES 72 (International Carnival of Experimental Sound) and the Stonehenge Free Festival of 1974 see themselves as soziale Plastik (social sculpture), and their influence on later subcultures, particularly in relation to public space, proves substantial.

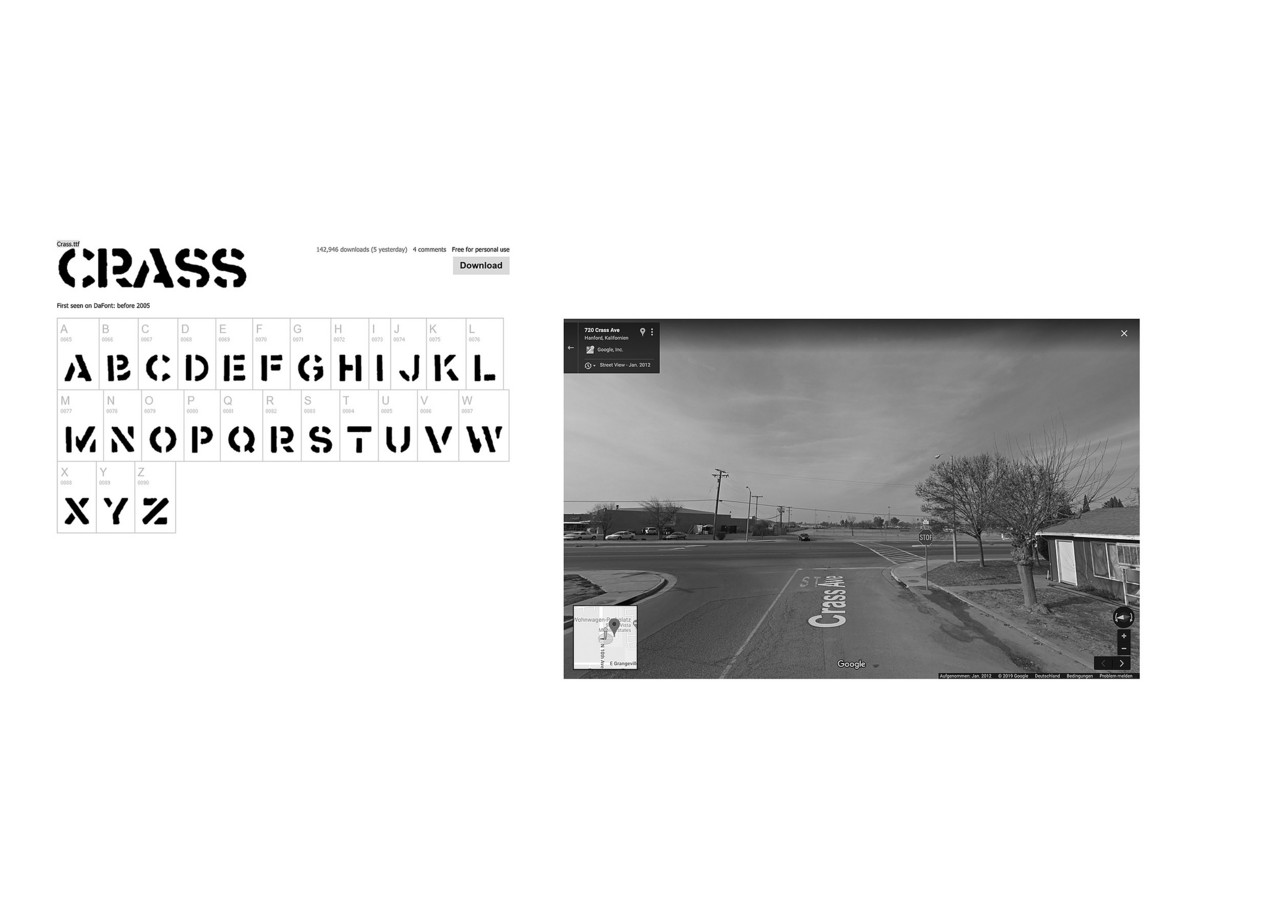

It’s 1977 now, and in reaction to the first eruption of punk in the UK, Penny Rimbaud and his 20-year-old Dial House-mate Steve Ignorant pull together a loose music collective with the aim of doing something a bit like punk. Tentative improvisation and a few recordings give rise to Crass, which quickly establishes itself as an authentic counterweight to a punk movement that is already selling out. Ignorant’s juvenile energy combines with Rimbaud’s theoretical foundations in a dynamic nexus that clearly puts its stamp on the further evolution of punk. Initially a cell of subversion, Crass soon becomes a prime example of anarchic self-management – and, incidentally, one of the most successful DIY businesses of the post-punk decade. Their records sell in tens of thousands and Crass concerts sell out faster than the Sex Pistols can break up. Rimbaud’s agitprop-inspired vision of consolidating links between art and activism to craft a social tool for the influence of politics certainly comes true. Crass becomes a critical voice in everyday British politics, taking a stance on everything from the Falkland crisis and social welfare cuts to gender inequality and animal rights. In response to ascendant Thatcherism, Crass turns the spotlight towards the mechanisms driving an increasingly pervasive, multi-national corporate capitalism.

Owing to a bogus interview tape, Crass goes under observation by MI5 in 1983 and splits up, as anticipated, in the Orwellian year of 1984. Yet despite turbulent times, Crass continues to return to Dial House, where Penny Rimbaud still runs his operations to date. Steve Ignorant describes how Rimbaud came to be at Dial House: »Pen’s idea of Dial House was that he’d seen a movie called The Inn of the Sixth Happiness set in Japan [it was, in fact, China] and they had these houses where you could travel from one to the next. And if you were a poet you earned your bed for the night by reciting poetry or if you were a cook you cooked a meal. I think the original ideology was to have places like Dial House dotted all over England, Wales & Scotland.«6 Evidently, Rimbaud was quick to see the importance of self-run autonomous locations dotted across decentralised network structures – locations that later became key in the squat movements of the 70s and 80s. Even then, when the appropriation of (primarily urban) spaces really gathers momentum, Dial House stays in the wings: avant-garde in strategic terms yet geographically under the radar.

It is with a similarly panoptic perspective that French sociologist Michel de Certeau opens his 1980 essay »Walking in the City,« describing how the city, when seen from the 110th floor of the World Trade Center in New York, is transformed into an »immense texturology spread out before one’s eyes.«7 Whether he thought about Crass at that moment is impossible to say, but it cannot be ruled out, as Crass played several gigs in New York that year. Gee Vaucher, who lived in New York at the time and was tasked to book shows for Crass, says, »I avoided booking the obvious. I said I’m not going to book CBGBs or Max’s. So I booked the Puerto Rican Club and the Polish Club.«8 That de Certeau hung out at CBGB during his time in New York is a little improbable. But it’s easy to imagine that one of his endless dérives in the city swept him into the Puerto Rican Club one night when Crass was on stage. Thanks to their common obsession with avoiding the limelight, de Certeau and Crass may well have run into one another, a case that would put flesh on the bones of de Certeau’s sketch of the city as a chance encounter of »paroxysmal places…clasped by the streets [and] possessed by the rumble of so many differences.«9 He thereby invokes a term from neoplatonic dialectics, coincidatio oppositorum:10 the coincidence of opposites. Here, the coincidence of opposites resolves the arbitrariness of the city as construct.

But to return to the idea of the city as text: the premise that urban planning, hypertext, and virtual space are structurally similar (as »path,« »link,« »node,« »interface,« »point,« »marker,« »intersection,« and similar terms suggest) is nothing new in contemporary media studies. The transition from the analogue to the digital has been equally as decisive in urban planning as for network research.

Yet we are in the year 1982. Now, from Dial House’s hippie grassroots approach sprouts the agile and efficient Crass Records, which shelters bands such as Rudimentary Peni, The Cravats, Flux of Pink Indians, Poison Girls, Zounds, and even Björk’s first combo, Kukl. And while all these bands are fired by the raw urgency of punk, their aesthetic and musical manifestations are highly idiosyncratic. Slapping on labels like »anarchic punk« or »peace punk« is handy for marketing, but what really melds all the artists on Crass Records’ roster is their shared faith in a liberal, utopian anarchy, and in the right of each and every individual to interpret and live as they please. This itself spawns the scene’s primary, vital network: bands now can go on tour and, once on the road, they forge links between otherwise-disparate places. For networking, countless hours are spent in copy shops, letters are handwritten, telephone calls are made by prior arrangement from public phone boxes. Everyone involved in those ventures is at least absolutely sure that the snail mail dispatched from A to B and beyond will be of immeasurable value to whoever received it.

Moreover, there is a byproduct of all these activities, for they leave behind a paper trail: linear streams of text channelling ideas and injecting new blood into the network sustain it and foster its growth. This communication – an architecture of the intellect, so to speak – is the very lifeblood of a fast-growing virtual network. The texts underpinning it hence acquire geographical import, consolidating thoughts and intentions in ways that shrink the spaces between villages, towns, and cities, building communities of like-minded souls. De Certeau’s primary premise, the city-as-text, is hence suddenly turned on its head. For now we have text-as-city – a city in which people have very consciously decided to live together, to trust one another, and to cooperate.

Next Stop: Mönchengladbach (and Then On to Venice by Boat)…

But let’s now leave the British Isles, return to 2019, and enter an address into Google Street View: Beethovenstraße 6, 4050 Mönchengladbach. This must ring a bell for anyone who ever laid their hands on a record by EA80: there hasn't been a more mythical German address in punk since 1981. The Beethoven reference and the post-war gloom that stubbornly pervades the town of Mönchengladbach on the Lower Rhine undoubtedly play their part. The fact is that EA80 has been permanently based there since 1981, with barely a change in line-up. This is a punk continuum of which Germany has never seen the likes before – a clandestine force field in Xeroxed black and white, melancholic, angry, and aggressive. Any hint of reconciliation is at a distant theological remove. Benjamin Moldenhauer once wrote in the German newspaper taz that »EA80 play in a league most people don’t even know exists;«13 and this is a fair comment on the non-place where EA80 has its roots: off the zeitgeist map, safe from co-optation.

Ever since, EA80 has done its thing as persistently as any exemplary socialist workers’ brigade could hope to. It has recorded 13 albums, released countless singles, and played in every squatted youth centre – never for more than a fiver, as is only right and proper for a punk band that feels morally bound to carry the cultural torch and pass it on to others in its network. This is almost conspiratorial, hence Moldenhauer’s remark.

And the background to the conspiracy is this: while punk in the UK grows out of a tradition in which pop culture is always in sync with a cultural industry that churns out youth cultures and markets them as products, the cultural landscape of post-war Germany is dominated by the Frankfurt School’s finer points of social analysis: a highly idealistic and cantankerously moralistic philosophy of right and wrong, authenticity and alienation, that lays a veil of cognitive dissonance across the land and soon culminates in both bitterness and a yawning generation gap. Even the radical movements that ensue – from the APO and RAF to the anti-nuclear movement – prove to be fertile soil for what is in essence an anti-hedonistic punk scene (and hence the very opposite of its UK counterpart). Acting in total refusal of social norms, the scene outrages the moral majority from the early 80s on, squatting the fountains of Germany’s market squares, swigging beer from bottles, and taking part in orgies of nihilistic self-destruction.14

But good things come out of battles on the margins. Every young generation must define its own freedoms; the urge to appropriate and defend space is always also a means of expanding it. That’s how houses get squatted and self-run youth centres get set up. These are places for fledgling communities committed to solidarity, equal rights, and sharing – for creating space beyond repression. And punk plays a role in this: it fuels many of those movements. Punk empowers the kids; it gives them energy, vision, and the chance to experiment with viable networks that are worlds apart from the mainstream dream. With »If the Kids Are United,« Sham 69 delivers a prophetic take on what punks should aspire to: namely to put an end to individuals’ isolation within the capitalist system, whether for a fleeting moment of personal freedom or for entire lifetimes.

But let’s get back to the hyper-capitalised present and see what’s going on over at Beethovenstraße 6, not that this address was ever an actual centre or public venue – just a postal address at which EA80 could be reached. The more you encountered it – whether through sending something to or receiving post from it – the more real it seemed, even without ever visiting. Over time, the text of this address became an emblem that conjures a picture of the place. And now, tracking it down via hyperlinks (thanks to Google’s virtual map), it’s possible to see how far reality and imagination overlap. But Google disappoints: Mönchengladbach doesn’t even feature on Street View, just like the many other towns in Germany too minor to guarantee a requisite number of clicks. Hopes of being beamed to a ghostly blurred house, a further facet in the EA80 myth, are suddenly dashed.

And there’s another building in Mönchengladbach. No more than a few streets away, and also hidden on Street View, is Unterheydener Straße 12 in the Rheyd district. The artist Gregor Schneider has (re)converted it many times over since 1985. Schneider has practically taken it apart, in fact, while managing somehow to retain its aura. The »Haus u r« concept, in which Schneider duplicated existing rooms within themselves, could easily have stemmed from EA80, but it is not known whether Schneider and EA80 ever met. In aesthetic terms, however, and despite their roots in contrasting cultural spheres, the two projects couldn’t be more alike. For one, Schneider too uses his house to communicate with the wider world. At the invitation of the Venice Biennale 2001 (respectively its curator, Udo Kittelmann), he reconstructs the entire building in the German Pavilion. Some 150 tons of building material are shipped from Mönchengladbach to Venice, to be resurrected there as »Totes Haus u r« [»Dead House u r«]. Thereafter, the project takes on a life of its own. Schneider tours with Totes Haus u r, travelling the art world in much the same way as EA80 travels the world of punk.

The comparison is rhetorical, of course, for a house is not a punk band. The point of this excursion is to fathom the utopian potential of certain places and, on the basis of that »immense texturology,« also the very letters that compose it. We drift – as in dérive – through the endless scope of contemporary multilocality while remaining focused on the individuals that link each point within it; the crucial factor here being the energetic structure of each place or – to cite Rupert Sheldrake – the morphogenetic field which psychogeographically underpins it and configures its synapses.

Even in 2019, however, punk is infinitely more than a spectral apparition. Whatever aura of anachronism it may conjure, and however often Google Street View depicts places like the Köpi as a blur, punk is still an ark on the rough seas of late capitalism. It is, perhaps, a phantom vessel adrift, but one nevertheless still willing to succour the motley non-conformists its network built over the past forty years – those united by the triumph of punk's idealism over the materialist world around it.

And the way this network operates is anything but anachronistic. The aforementioned communication skills of the still-analogue world have been transposed to the digital present without frictional loss – and are able now to turn over much more information at far quicker speeds. True, bands today still have to lug their backline from venue to venue to play live for audiences that trek home happily clutching some handmade merch. Yet on the whole, things suddenly became a lot more peer-to-peer and direct. So if, say, the Berlin punk scene’s Facebook page, Pech gehabt Keule!,16 had announced yesterday that Cuntroaches would be playing at the Köpi tomorrow, word would have spread like wildfire and comments would be posted too. Likewise, if projects and squats like the Potse, Drugstore, or Liebig 34 were about to be evicted, instant response, activity, and feedback would be guaranteed. Because nothing but feedback can ever cut through the compartmentalised dimensions of time and space to forge vital spaces of collective experience.

- 1

George Berger, The Story of Crass (Oakland: PM Press, 2009), p. 78.

- 2

Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984); translated by Steven Randall.

- 3

Berger, The Story of Crass, p. 93.

- 4

de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, p. 91–92.

- 5

Coincidatio Oppositorum is a term from medieval theology which psychoanalysis has preserved for contemporary usage and which Michel de Certeau subsequently adopted and adapted for this essay.

- 6

George Berger, The Story of Crass (Oakland: PM Press, 2009), p. 78.

- 7

Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984); translated by Steven Randall.

- 8

Berger, The Story of Crass, p. 93.

- 9

de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, p. 91–92.

- 10

Coincidatio Oppositorum is a term from medieval theology which psychoanalysis has preserved for contemporary usage and which Michel de Certeau subsequently adopted and adapted for this essay.

- 11

Benjamin Moldenhauer, »Was geblieben ist«, 12.1.2013, taz – die tageszeitung, Bremen Aktuell, p. 47.

- 12

A thorough documentation of this state of affairs is available on the extremely entertaining archive platform run by Karl Nagel.

- 13

Benjamin Moldenhauer, »Was geblieben ist«, 12.1.2013, taz – die tageszeitung, Bremen Aktuell, p. 47.

- 14

A thorough documentation of this state of affairs is available on the extremely entertaining archive platform run by Karl Nagel.

- 15

The full name of the Facebook group is: »PECH GEHABT KEULE! AKA PICK YOUR PARTY BERLIN punk, etc.«

- 16

The full name of the Facebook group is: »PECH GEHABT KEULE! AKA PICK YOUR PARTY BERLIN punk, etc.«