Words strut about and make a space for themselves. They rise out of the conversation with other words to temporarily colonise language and determine interpretations, enforcing new contexts and meanings, carrying through ideologies and desires that are the driving force of their upsurge.

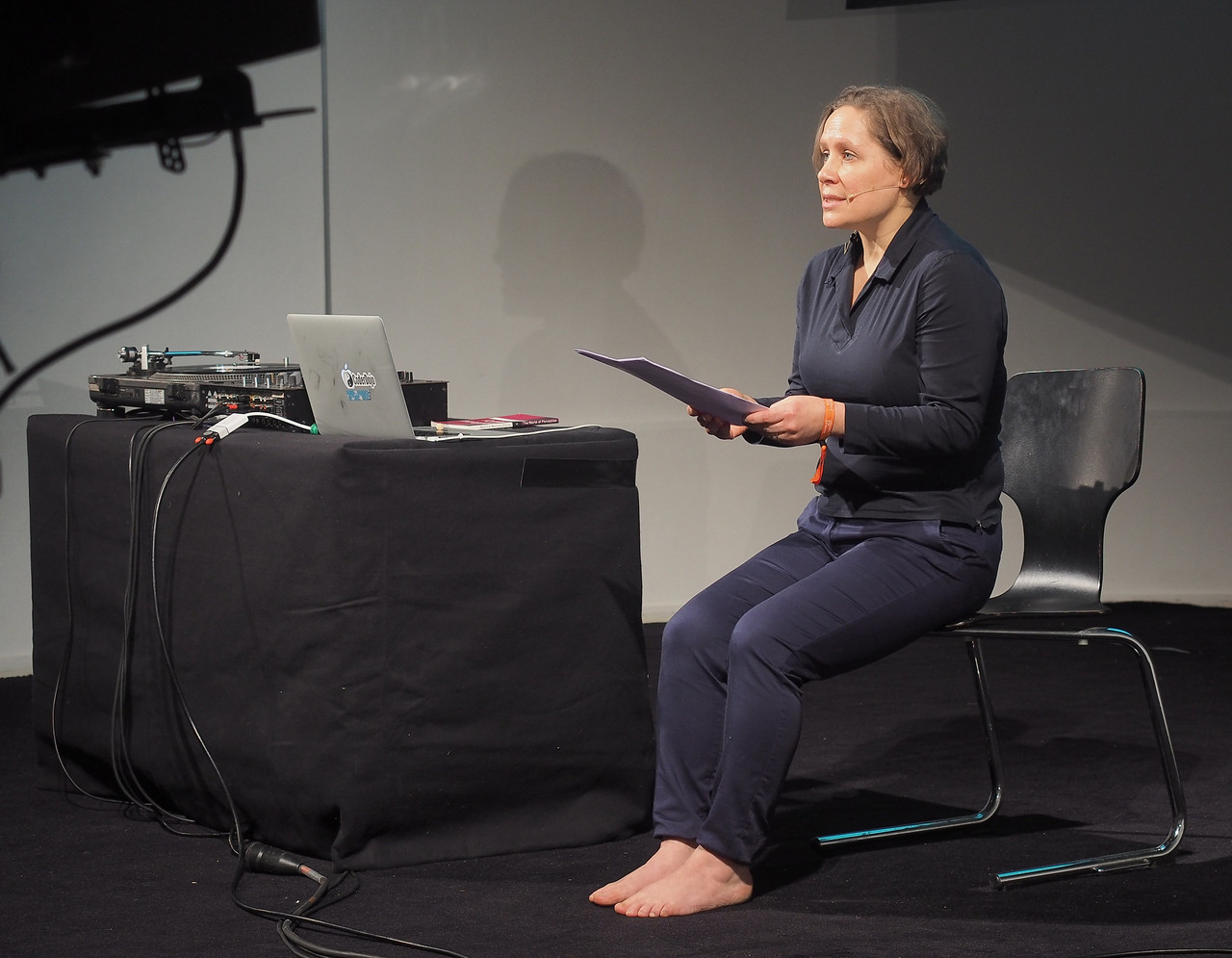

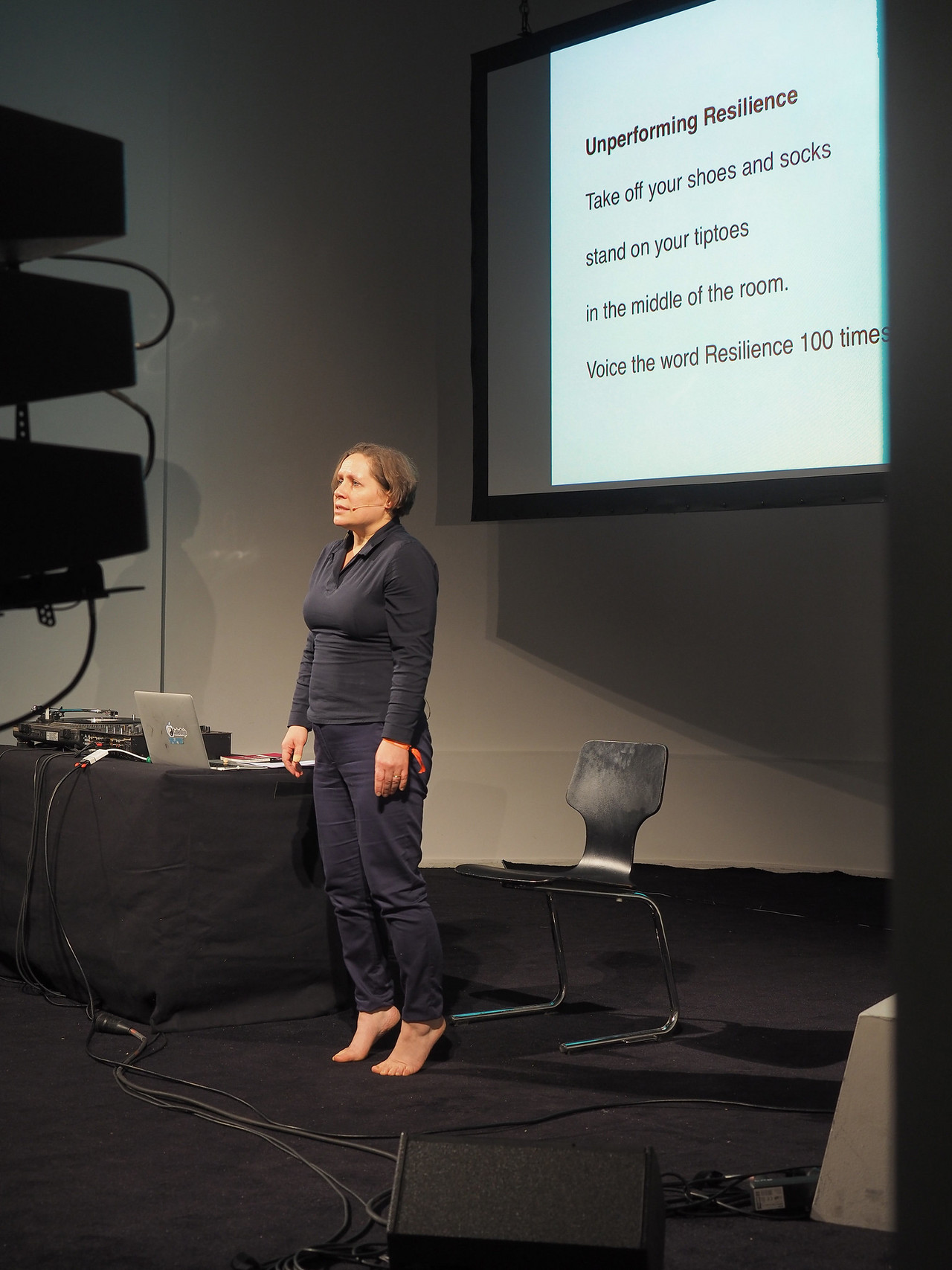

However, words also stutter and fall over themselves, breaking the rhythm of their naturalised meaning, and, suddenly sounding awkward, they expose the ideologies that carried their prominence. And so, standing unsteadily on bare tiptoes, Resilience falls over its own repetition to reveal what it knew all along: that it was a con, a charade, played out on the back of those who had no choice but had become persuaded by its ever more frequent repetition and the promise of its rhetoric to provide agency and security in a baffling and abusive world. Resilience connotes »the capacity of a system to return to a previous state, to recover from a shock, or to bounce back after a crisis or trauma.«*1) This resilience is ideational. Bouncing back should occur without the help of social infrastructure, but through training and anticipation instead. It is a signifier of individual strength and autonomy that interprets elasticity as compliance (i.e. to accept low wages, precarity, uncertainty, disaster, and even war), and demands you withstand it on your own two feet. Its emphasis is on an ethics of self-care and self-entrepreneurship that balances the financial deficit on the weakest in society, and distracts from other political possibilities by pronouncing an ongoing threat that demands preparedness rather than resistance.

Repeating Resilience over and over on shaky ground, however, this emphasis slips. And once accidentally »mispronounced,« with a stress on the soft vowels and a skip of the consonants’ edge, its politics becomes apparent. This sonic slip-up offers a glimpse behind the scenes, at the engine and author of its aim: the neoliberal ideal for the individual to become »a subject which must permanently struggle to accommodate itself to the world, and not a subject which can conceive of changing the world.«*2) A subject, in other words, that overcomes its own weakness rather than fighting the inequities that cause it; that cannot resist, but needs to adapt, thereby inadvertently enabling the status quo that is stacked against it.

By contrast, in our unperformance of vowels and consonants, in an extended and unnatural pose, on the tips of our toes, we expose the development of a word from the scientific sense of ecological adaptation into a dubious economic elasticity: instituting the neoliberal response to asymmetrical resourcing that prepares the mind and body for the tolerance of an intolerable world, offering solutions on the stretched-out form of the resilient individual without having to address causes or consequences, thereby abdicating collective responsibility in favour of personal blame.

However, in the breathy enunciation of E’s and I’s without language as a certain frame to lean on rests another meaning: that of failure and vulnerability, which become radical efforts of resistance in an unequal world. And in the fragile breath of their open sounds, politics finds another imagination: that of a shared existence and responsibility, performed in the acknowledgement that there is no independent self but that everything, including every »I,« is made of non-»I«, non-thing elements:*3) My tiptoed voice repeating Resilience 100 times articulates between body and breath, and sounds the co-dependence of oxygen and the sun, of trees and water, life and things. Thus it brings home the need for collaboration and participation and sounds an elasticity that is not resilient, but expansive and contingent.

In its repeated performance, Resilience rethinks the neoliberal adaptability of the individual in the invisible volume of sound, its viscid dimensionality, where responsibility is not individuated but a matter of interbeing, as being of and with each other: not »this« or »that« but »this« with »that« and from »that,« indivisibly sounding a shared cosmos; and where weakness is not overcome but listened to, sounded and heard in the breath that connects us all.

The volume generated in the unperformance of Resilience is not a measure of decibels but the expanse of a sonic world, its voluminous capacity, generated by our collective sounding and listening, in all its asymmetries, terrors, and dangers, but without allowing them to singularise the political imagination. This is not a capacity to endure, but a capacity for interaction and the possibility of a shared cosmos.

According to Mark Thatcher and Vivian A. Schmidt, writing in Resilient Liberalism in Europe’s Political Economy, resilience is »perceived as the only legitimate course of action.«*4) It pretends to allow for diversity and plurality, everybody can be resilient, while remaining the only possibility, everybody has to be resilient. We have accepted this demand since its solution appears simple: »she must learn resilience«*5) while not questioning its unyielding elasticity, whose flexibility is not a sign of its conceding and reciprocal intent but the rationality of its control.

By contrast, the sounds of our unperforming Resilience are irrational in relation to the word’s neoliberal aim. Its enunciations do not move on a horizontal chain of meaning and association but dive into the depth of contingent articulation. They produce a verticality of sense, »embracing a world of forces and matter, which lacks any original stability,«*6) and linger in an elastic expanse that is that of sound rather than of compliance. Here we do not hear the rhetoric of one truth and the demand of its reality, but plural possibilities that initiate other ways to live: where she does not have to learn to be more resilient, but comes to resist the cause of her pain.

To follow the vertical, to fall vertiginously into the word, is to discover its invisible textures, not to a certain ground but into a viscid expanse, in which we inter-are with things in our individual capacities together. Thus through its repeated performance, Resilience starts to open a different imagination that rethinks neoliberalism’s adaptability of the individual through the possibility of an indivisible world and the necessity of radical nonresilience.

Thatcher and Schmidt wonder whether there is already a different political economic imagination afoot. They sense a tipping point but concede that they are not sure. They suggest that »on the one hand, the content of neoliberal ideas may be weakened from the inside by its increasing internal incoherence and gaps between rhetoric and reality,« and that »on the other hand, rival ideas may gain strength.« In the conclusion of their 2013 publication they mention the concurrent developments in Latin America and Barack Obama as sources for a potential rethinking of the neoliberal ideal – neither of which have succeeded, however. But Thatcher and Schmidt leave us with hope by suggesting that a new thinking »might arise from novel sources…«*7)

I understand the nonresilient elasticity of sound to be such a novel source for a radical critique and agitation of resilience that as neoliberal signifier enslaves and blames us individually, but that as repeated utterance creates a voluminous expanse and makes us responsible together. Sound, a sonic sensibility, does not provide the consciousness of a counter-resilience but enables its unperforming, its re-articulating, re-uttering, in bits and pieces of separate vowels and consonants that form a volume which we can inhabit together in a contingent process of co-constitution, trying at least to listen out for and participate in a more equitable world.

And here I meet Thatcher and Schmidt’s hope for a Latin American source of another thinking as I hear in the avant-garde compositions of Jocy De Oliveira the soundscape of a sonic possible world that is viscous and indivisible, promoting a being-together according to listening and sounding without a horizon of danger but the possibility of a different future.

De Oliveira, a Brazilian composer, musician, artist, and writer, began her career as a concert pianist playing the works of avant-garde composers such as Berio, Xenakis, and Santoro. During the 1960s, however, she started to focus on her own compositions, which expand a traditional definition to cover installation, film, video, and theatre as well as concert hall works. And as little as her sonic works comply with a traditional definition of music, so too do they not comply with the neoliberal disaster management of economic asymmetries, but sound on slow revolutions a vulnerability that connects rather than needs to be overcome.

Her work presents a »novel source« to rethink resilience through voices, electroacoustic sounds, and acoustic instrumentation. They sound the world as a voluminous cosmos and create the condition and impetus for a different engagement. And so as I listen to undulating voices, breathing words, and moving sounds, I accept an invitation into »a distinct cultural capsule, and a means through which to find accurate truths to amend history’s sins.«*8) Her work generates the material for a global conversation that rethinks reality and truth through sonic rather than ideological encounters.*9)

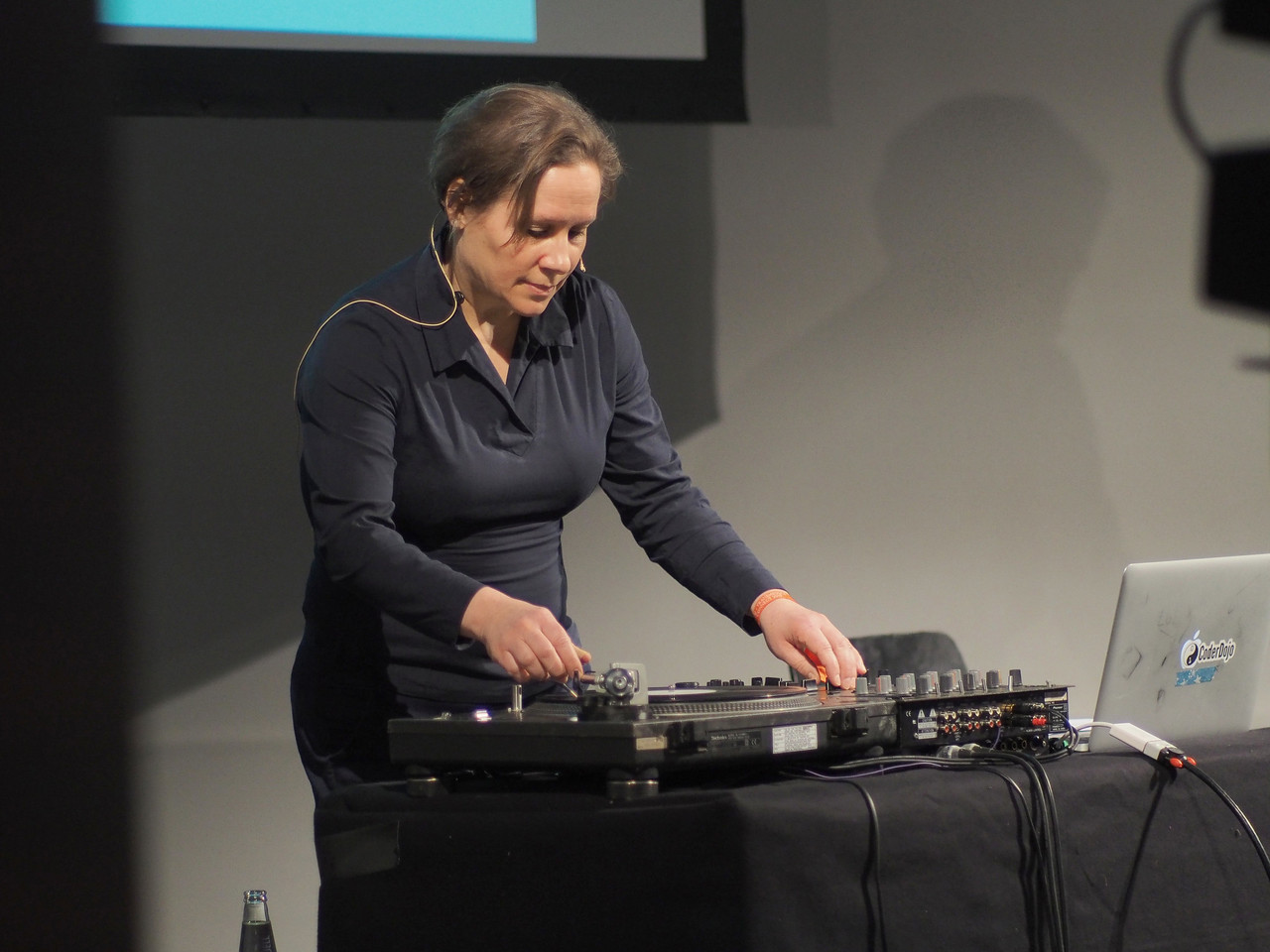

De Oliveira’s work spans seven decades and in that time sounds different socio-political realities and possibilities. I am listening to »Estória IV,« a composition which she started in 1978 and first released in 1981, during the last years of the military dictatorship in Brazil. Its performance occupies the whole second side on the album Estórias Para Voz, Instrumentos Acústicos e Eletrônicos (stories for voice, acoustic and electronic instruments), an album which in its 2017 re-release is a bright and translucent red. No visible lettering or labels, just a bright-red turning surface that makes no line of tones but a volume of voices and sounds, open-mouthed and moving, one performer singing after the other, following the same text not to understand but to modulate and exist in the encounter: indivisibly, expansive, and potentially infinite. As De Oliveira, discussing the piece, explains: »the performer’s role is not to make the text understandable but to use it as a key, for the phonemes selection, singing as slowly as possible, as a tape that has been played backwards, in a slower rotation.«*10)

The piece turns these two voices around the deck, around the mouth in slow rotation, articulating between Portuguese, Sanskrit, and Japanese expressions a language that is nobody’s and everybody’s; that in its turning undulation explores and performs the sonorous depth of words rather than their horizontal connection in language, and that sounds without recourse to semantic certainties another possibility of sense.

The sound created between the two voices, electronic violin, bass, guitar, and percussion is elastic without being compliant. It does not adapt but formlessly forms another imagination of music, of instrumentation as well as of the body, and also in extension of the political understood as the governance of interaction and living together. It creates communication as a viscous thread that repeats and returns again and again to the same juncture without saying the same, but pointing at the infinity of expression and the impossibility of a direct exchange. This impossibility is not the work’s failure but its desire for a plural voice, and its infinity is not a sign of the work’s resilience, but the continuation and expanse of its viscid material and song.

Bradford Bailey, writing in the liner notes of the album, reminds us of the paradox of the avant-garde, and particularly the Latin American avant-garde: of its optimism and global exchange post-war – »bouncing and ricocheting around the world, these sounds, structures, and ideas, have offered a forum through which radically diverse backgrounds and cultures can meet and speak« – and its concurrent inability to reach a broad audience and become part of a general socio-cultural consciousness – the failure of its »quest for open democracy and access through sounds, it is a world which, for most, remains opaque – perceived as offering challenges too great for the majority of listeners to take.«*11) Thus while this work remains relatively hidden still, its audition in the context of a discussion on resilience allows us to reconsider its sonorous power. It invites us to think about what might have been if it had succeeded in its quest and had managed to inculcate a general listening and broad sonic consciousness of the world at this very moment, in the 1970s, when neoliberalism was finding a footing in politics and language, and a truth in the breathless preparation for disaster and catastrophe via ecological notions of adaptability.

By contrast, the truth of this sound is that of its material and of its performance. There is no manipulation on the tape that provides the original for this record re-release. Instead, the tape faithfully provides the surface for the depth of an elastic sound. This faith is not that of resilience, but of resistance to the status quo, that of music, that of language, and that of politics. Its truth is complex because it is contingent. It does not promise an understanding and the clarity of easy solutions, but practices the demand of a sonic depth, where we need to generate our own understanding and participate. It provides not a line of words but a volume for us to be in, together, to breathe in its slow rotation and to share in the indivisible cosmos of its sonic expanse.

»Estória IV« produces an elastic sound that unperforms resilience. That counters the pliability not with a stubborn refusal but with the resistance of the material to be plied into a form, by not accepting to work with what can be listened to and instead making us hear something new.

And so to practice our tiptoed unperformance of resilience we can join with De Oliveira, following her first voice, modulating with it to find our place in a fragile and open sound, going round and round on the record deck not to show stamina and acceptance but vulnerability, and to produce with our voice a different sound that resists the pull of forward movement, simplicity, and self-care, and relishes the rotation and fleeting encounters with everything. Not to move towards a certain aim but to move in processes and relationships, to experience in their depth an unresolvable fragility rather than a weakness to be overcome.

And maybe if in the 1970s, the moment financial politics took resilience from the discourses of ecology to adapt to its own aims, we had learnt to listen to avant-garde music in general and the work of Jocy De Oliveira in particular, we could have avoided a descent into insecurity and resilience and practised our own voices, our own breath, generating an autonomy that is not about self-care and responsibility, but about creating an environment for everybody and everything.